Oryahovo, Bulgaria

This is part 2 of the mourning tour. I’m not so interested in fortresses or military history but it was a lovely place to walk around in and it’s a big part of Belgrade history.

Ru

|

Silicon (e) Valley Our guide asked us why we though this area was called Silicon Valley. Rick guessed it had something to do with computers. Randal joked and said it’s where all the women have silicone implants. Randal was right. “At midnight the street of Strahinjica bana on the edge of the old town is packed with people and cruising cars with tinted windscreens. The street is known locally as "Silicon Valley" for the number of surgically-enhanced trophy girlfriends on display.” “Cafés and bars in Strahinića Bana Street, locally known as "Silicon Valley", are the fanciest in Belgrade and people usually come here to see and to be seen, especially if you are owner of a smart car and wish to park it ostentatiously close to your chosen venue.” http://www.belgradenet.com/belgrade_cafes.html Serbia’s nouveaux riches By Jacky Rowland in Belgrade Wednesday, 9 February, 2000, “The recent killing of the notorious Serb paramilitary leader and gangster, Zeljko "Arkan" Raznatovic, has thrown the spotlight on the new financial elite in Serbia. These are people who have made their money in the last 10 years, through dubious business deals and by busting international sanctions against Belgrade. The huge wealth amassed by this small group of individuals has given them considerable power and has put them above the law. The nouveaux riches like to flaunt their money, but they do not want to discuss where it came from. They call themselves "businessmen" – business which often consists of smuggling, black marketeering and protection rackets. International sanctions which punish ordinary people are enriching these entrepreneurs. The opposition is screaming for the embargo on oil and other goods to be lifted, but many people in high places are quite happy for it to remain. These people have so much money they don’t know what to do with it. They’ve bought houses, they’ve bought cars, now they want to buy back their youth. The nouveaux riches can be found in the few select shopping malls in Belgrade. That is where Italian designer boutiques offer solutions to the dilemma of how to spend one’s cash. The prices here would raise eyebrows even in London: it is easy to spend twice the average monthly Serbian income on a pair of shoes. There has been an upsurge of interest in cosmetic surgery among Serbian high society.

A number of politicians’ wives have benefited from appearance-enhancing treatments, including breast implants, liposuction and "nose-jobs". "These people have so much money they don’t know what to do with it," says Bratislav Grubacic, a political analyst. "They’ve bought houses, they’ve bought cars, now they want to buy back their youth." Education and spiritual values don’t count in Serbia today. All that counts is money and material things, and it doesn’t matter how you get them. There is no shortage of wannabes: young men and young women who see Arkan and his lavish lifestyle as a role model. Many girls have embarked on a career as a model in the hope that their looks will take them places, preferably away from Serbia. In the meantime, there is at least the chance of earning some decent money: a model can earn more in a day than a factory worker earns in a month. "Education and spiritual values don’t count in Serbia today," said Nebojsa Grncarski, a successful male model. "All that counts is money and material things, and it doesn’t matter how you get them." http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/633920.stm Even in 2014 this pretty much what our tour guides said was true. |

|

This bar, around the corner from “silicon valley” was popular during days of communism and is still popular with no stigma attached. Serbia had ‘soft” communism so it is viewed differently. |

|

The Manak’s House (Manakova kuća) – The house was built in 1830 and has been preserved as the last surviving example of an old Belgrade town house. It got its name from its owner Manak Mihailović, a merchant from Macedonia. The first floor was used as a residence, while the ground floor housed an inn and a bakery, and later a post office and various tradesmen’s workshops. Today it is a museum housing an ethnographic collection. http://www.jobeograd.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=79&itemid=102 Manak’s House treasures exceptionally valuable ethnographic memorial collection of Hristifor Crnilović. This house of irregular shape is a venue of the Ethnographic Museum and an example of old urban architecture in the Balkans. Today exhibitions and workshops for learning old trades are being organized here. Manak’s House originates from the year of 1830 and there are numerous stories about its origin. According to one of such stories, the house was built as a harem of the Turkish aga who left Serbia after the arrival of Prince Miloš Obrenović. For some time the house served as the post office, and later it was bought by Manojlo Manak who opened a bakery and a kafana (traditional tavern) at the ground floor and the first floor he used for living quarters. Nevertheless, the house was named after Manojlo’s cousin from Macedonia and his inheritor, Manak Manojlović. Its irregular shape was conditioned by the shape of the parcel in Savamala, on the old road that connected this settlement with Varoš kapija (today’s Kraljevića Marka Street, no. 10). http://www.serbia.com/manaks-house/ Hristifor Crnilović – explorer, painter and collector http://www.serbia.com/manaks-house/ tells his really interesting story. “Most of the items from the collection he collected between the two world wars, while working as a teacher in Skopje. At the beginning of each summer break he would buy a horse and he would visit villages in Macedonia and Southern Serbia. With great passion he collected different items that testify on customs and people living in the late 19th and at the beginning of the 20th century.” Real zebra crossings. In Belgrade cars must stop for pedestrians at zebra crossings unless there is a light also which takes precedence. Someone had painted real zebras around what is now a children’s school. |

|

The Bajrakli Mosque The Bajrakli Mosque in the centre of Belgrade, in Gospodar Jevremova street, got its name from the flag (Turkish, bayrak) that signalled the call to prayer to other mosques. As the endowment of Sultan Suleiman II, it is the only remaining mosque of the many that once existed in Belgrade. It was built between 1660 and 1688 and is of the type with a square floor-plan, single interior space and a dome resting on an octagonal tambour. It is built of stone, except the minaret which is brick. During its history it has been demolished or its function changed a number of times. It was originally called Čohadži Mosque, after its benefactor, a textiles (čoha) trader called Hadži-Alija. It was a structure with a single interior space, dome and minaret. During the period of Austrian rule (1717-1739) it was turned into a Catholic church. This period also saw the majority of Belgrade’s mosques destroyed. Upon the return of the Turks it once again became a mosque. Hussein-bey, assistant to Turkish chief commander Ali-pasha, restored it as a place of worship in 1741 and thus for a time it was Hussein-bey’s (or –beg’s) Mosque or Hussein-ćehaja’s Mosque (ćehaja means assistant). After its restoration in the 19th century, which was undertaken by Serbian noblemen, it became the central city mosque. Today it is the only active Muslim place of worship in Belgrade. |

|

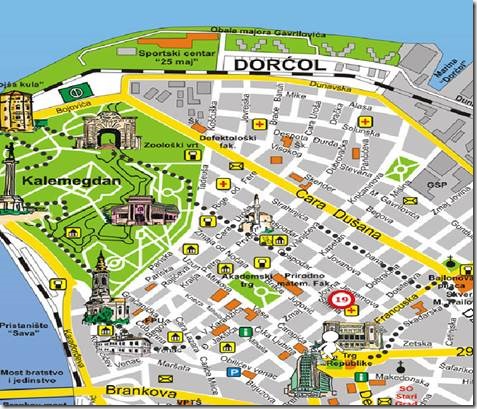

Our next stop was the Fortress of Belgrade which, once upon a time, was the city of Belgrade, everything within the walls of the city. http://www.leisureguide.info/portal/index/company/634578?category_id=22 has great photos and tells you everything you might want to know about this Fortress, its gates, walls and buildings. The Sava is on the left and the Danube is perpendicular to it on the right. Belgrade Fortress “The Belgrade Fortress was built as a defensive structure on a ridge overlooking the confluence of the Sava and the Danube during the period from the 1st to the 18th century. Today the fortress is a unique museum of the history of Belgrade. The complex is made up of the Belgrade Fortress itself, divided into the Upper and Lower Towns (Gornji/Donji grad) and the Kalemegdan Park. Because of its exceptional strategic importance, a fortification – a Roman ‘castrum’ – was erected here at the end of the first century A.D., as a permanent military camp for the Fourth Flavian Legion. After being razed to the ground by the Goths and the Huns, the fortification was rebuilt in the first decades of the sixth century. Less than a century later it was demolished by the Avars and the Slavs. Around this fortification on the hill above the Sava and Danube confluence, the ancient settlement of Singidunum grew up, followed by the Slav settlement of Belgrade in the same place. The Belgrade Fortress has frequently been demolished and rebuilt. On top of the Roman walls stand Serbian ramparts on top of which are Turkish and Austrian fortifications. In the 12th century the Byzantine Emperor Manuel I Comnenus built a new castle on the Roman ruins. During the first decades of the 14th century this small hill-top fortification was extended as far as the river banks. Under the rule of Despot Stefan Lazarević, Belgrade became the new capital of Serbia and was fortified by the addition of the extensive fortifications of the Upper and Lower Town. The Despot’s palace was built in the old castle, and a military harbour was added on the Sava River. An advanced mediaeval city developed within the ramparts. A new era began with the Austro-Turkish War. As a key fortification at the heart of the fighting during the 18th century, the Fortress was rebuilt three times. The old castle was demolished and a large part of the mediaeval walls were covered by new fortifications. Under the Austrian occupation from 1717 to 1739, and after the construction of new modern fortifications, the Belgrade Fortress was one of the strongest military strongholds in Europe. It was built to plans drawn up by Colonel Nicolas Doxat de Démoret, a Swiss serving in the Austrian Army. By a quirk of fate the builder of the fortress was shot right in front of the fortress walls at dawn in March 1738, because of the defeat of the army at Niš. Prior to the return of the Turks to Belgrade in 1740, all the newly constructed fortifications were demolished. By the end of the 18th century the Belgrade fortress had taken on its final shape. Nearly all the buildings in the Upper and Lower Towns were destroyed in the fighting during the previous decades and the walls were badly damaged. Two streets, Knez Mihailova and Uzun-Mirkova lead to the Belgrade Fortress. The two main gates on that side are the Stambol Gate (Stambol-kapija) (inner and outer) and the Clock Gate (Sahat-kapija). The mediaeval fortress was entered from the east (alongside today’s Zoological Garden), through the Prison Gate (Zindan kapija) and the Despot’s Gate (Despotova kapija) in the Upper Town. The Lower Town is approached via Bulevar vojvode Bojovića (via the Vidin Gate – Vidin-kapija) and from Karađorđeva street (the Dark Gate – Mračna kapija). |

|

Zindan Gate Complex “This semicircular fortification – the Zindan Gate Complex was built in the middle of the fifteenth century, in front of the Despot Gate. It consists of arched gates having two rounded towers and a bridge. The gate has, along with massive doors with wings reinforced with iron, auxiliary rooms as well. The Zindan Gates are identical in shape and purpose, but there are not connected in any way. The upper part of the towers ended with tines because of specially built screens, the so-called ‘musarabije’ (meaning “nose for tar”) or ‘masikula’, which were very efficient and functional in repelling the enemy beneath the tower’s walls. The towers had more levels which were interconnected. The Turks used the towers’ basement as dungeons for Christians. Hence the name for the whole complex (Turkish word ‘zindan’ stands for dungeon). The towers were reconstructed in 1938.” http://www.leisureguide.info/portal/index/company/634578?category_id=22 King Gate “The gate was built within the south-western rampart, in the period between 1693 and 1696. It got its final shape during the Austrian reconstruction of the Fortress in the first decades of the eighteenth century. The gate has a baroque appearance, with a half-vault and rooms located at the inner side of the rampart. At the outside of the gate there is a bridge tiled with wood bricks which replaced the former construction of wooden bridge in 1928.” http://www.leisureguide.info/ One of the churches within the fortress. Looking out over the Sava River This lovely stone building is now the office/workshop of archeologists who Do Not Want Visitors as It’s Not A Museum. I found this out when I went in to ask. Too bad because it looked really interesting but then I guess they’d never get work done of some visitor would break something. |

|

The Victor Monument This is a humorous telling of the Victor monument’s saga, but pretty much matches what our tour guides told us. “The Victor monument, the most famous Belgrade landmark ended up in Kalemegdan by chance. It was previously planned to place the monument in the middle of Terazije square, together with two other smaller statues as a part of a grandiose monument complex that was supposed to be our version of Triumphant Arc – a symbol of Serbian victory over the conquerors in the Balkan wars. But, just before everything was ready, the First World War broke out and the plan was postponed, everything but the Victor destroyed or never finished, and the plan had to be changed. Not only that, but somebody noticed that the monument was, well, naked, and that it didn’t look very Serbian (I don’t know if they were referring to his nose or something else) so the city authorities placed him at the most secluded Kalemegdan part they could think of. Legend says that his frontal part was pointed towards the defeated Austro-Hungarian empire and the background towards the Ottoman empire, which indeed makes sense when you think about it.” http://www.belgraded.com/the-victor-monument-kalemegdan |

|

While at the Fortress we were told the early history of Belgrade and shown the location of the Roman wells. Many of the tunels under the fortress are blocked off since some teenagers went wandering around in them and not all came out again. The Princess lived here while the Prince lived elsewhere with his mistress, or so we were told. The Residence of Princess Ljubica, built in 1831, is a rare preserved example of architecture from the time of Prince Miloš Obrenović (1783–1860). The wife of Prince Miloš, Princess Ljubica lived there with their sons Milan and Mihailo. The Residence is presently a museum housing the permanent exhibition “Interiors of Belgrade Homes in the 19th Century”. The development of the modern Serbian state and Belgrade’s transformation from an Oriental city to a modern European town can be traced in the transitions of interior decoration styles in the homes of sovereigns and prominent 19th-century Belgrade families. With its furniture and other household stuff typical of the early 19th-century houses in Belgrade, like benches, the dinner table (sofra), a low round table (sini), a brazier (mangal), and Oriental cookware, the room of Princess Ljubica reflects the earliest stage in that process. It is flanked by the Little Hamam and the Great Hamam (Turkish baths). The Little Hamam, the only room in the Residence adorned with wall paintings, is decorated in the Rococo Revival style. The other interiors presented within the permanent exhibition show the features of various Western and Central European decoration styles that came into use in Serbia throughout the 19th century: Biedermeier, the Second Empire style, Baroque Revival, Rococo, Alt Deutsch, etc. The permanent exhibition also presents 18th- and 19th-century engravings of Belgrade and Serbia, as well as numerous portraits of Serbia’s 19th-century rulers and prominent citizens. |

|

St Michael’s Cathedral The Cathedral Church of St. Michael the Archangel (Serbian: Саборна Црква Св. Архангела Михаила, Saborna Crkva Sv. Arhangela Mihaila) is a Serb Orthodox Christian church in the centre of Belgrade, Serbia. It is one of the most important places of worship in the country. It is commonly known as just Saborna crkva (The Cathedral) among the city residents. http://mybelgrade.net/item/st-michaels-cathedral/ Museum of the Serbian Orthodox Church is housed in the Patriarch’s residence The Patriarchate (Patrijaršija) building houses this collection of ecclesiastical items, many of which were collected by St Sava, founder of the independent Serbian Orthodox church. Read more: http://www.lonelyplanet.com/ Until 1054 AD Eastern Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism were branches of the same body—the One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church. This date marks an important moment in the history of all Christian denominations because it designates the very first major division in Christianity and the beginning of "denominations." Disagreement between these two branches of Christendom had already long existed, but the widening gap between the Roman and Eastern churches increased throughout the first millennium with a progression of worsening disputes. On religious matters the two branches disagreed over issues pertaining to the nature of the Holy Spirit, the use of icons in worship and the correct date for celebrating Easter. Cultural differences played a major role too, with the Eastern mindset more inclined toward philosophy, mysticism, and ideology, and the Western outlook guided more by a practical and legal mentality. This slow process of separation was encouraged in 330 AD when Emperor Constantine decided to move the capital of the Roman Empire to the city of Byzantium (Byzantine Empire, modern-day Turkey) and called it Constantinople. When he died his two sons divided their rule, one taking the Eastern portion of the empire and ruling from Constantinople and the other taking the western portion, ruling from Rome. In 1054 AD a formal split occurred when Pope Leo IX (leader of the Roman branch) excommunicated the Patriarch of Constantinople, Michael Cerularius (leader of the Eastern branch), who in turn condemned the pope in mutual excommunication. http://christianity.about.com/od/easternorthodoxy/a/orthodoxhistory.htm |

|

Tugba and Emre from Izmir, Turkey were also on the walking tour. Our guides were sensitive and tactful when speaking of the wars between Yugoslavia and the Ottoman Empire |

|

Question Mark Café - see the question mark over the door The Question Mark Inn (Kafana "?") – This building close to the Cathedral and Patriarch’s Home, in typical Serbian-Balkan style, was built in 1823 from the materials that were then in most common use – wood and clay. The building has changed owners (including Prince Miloš Obrenovic) and purpose on a number of occasions, but mostly it served as an inn. Its name varied through the time: "Tomina kafana" ("Toma’s Inn"), "Kod pastira" ("At the Shepherd’s"), "Kod Saborne crkve" ("At the Cathedral"), until eventually the church authorities requested that the inn sign be removed as "a sacrilege against the Church of God." The owner then put up a temporary sign with a question mark which has remained its name to this day. http://www.jobeograd.org/ We had some lunch of bread, Serbian curd cheese, and cabbage rolls. |