|

Life under Communism and how people look back at that sometimes with nostalgia. Article below…..

“The Germans have a great expression for life in a competitive, dog-eat-dog country. They call it an “elbow society.” People in capitalist countries have sharper elbows, and they use them more readily.

In Bulgaria, some people look back on their time during communism, the time before the introduction of the elbow society, as the “calm life.” You generally didn’t have to work hard. You didn’t have to worry about losing your job. Life was simpler. There was only one kind of washing powder. You could count the number of television channels on one hand.

In retrospect, the calm life has a certain appeal. If you’re out of work or going crazy because of multitasking or feel the hot breath of a competitor on your neck, the old days begin to feel almost like a holiday: boring perhaps but not so stressful. Of course, as with all nostalgia, these memories are selective. The painful memories tend to be suppressed.

Petya Kabakchieva is a sociologist who has done research on a number of social issues in Bulgaria. One of her first topics was social status associated with work

“People knew that their salary didn’t depend on their effort,” she told me over dinner at a very good restaurant in Sofia with an old Art Nouveau interior. “They worked, but they didn’t invest a lot of effort. In my research after the change, a lot of people told me, ‘Now we will work with pleasure, because we are working for ourselves. We will not depend on the state salary.’ At the moment the opposite is happening — a lot of people are feeling nostalgic about the fixed salary, because there is a lot of unemployment and poverty. This means that something in the so-called ‘transition’ went wrong.”

She has done research on a number of fascinating topics: on the construction of memories, on temporary migrants, on Roma integration. We talked about her sociological investigations as well as her own personal experiences and her evolving understanding of “the People,” from her time in Leipzig in 1989 to her view of Bulgarian society today.

The Interview

When you look back to 1989 and everything that has changed between now and then, how would you evaluate that on a scale of 1 to 10, with one being most dissatisfied and 10 most satisfied?

Those are the questions I hate the most! It is very difficult to evaluate your memories, experience, and feelings on a scale…Anyway, I’ll try to answer. Usually, at least in Bulgaria, people say 5. But you cannot interpret this number, because it means, simply, “I don’t know.” So, I would say 7.

Same scale, same period: how would you evaluate your own life?

10.

When you look into the near future, where do you think Bulgaria will be in 1-2 years, on a scale of 1 to 10, with 1 being most pessimistic and 10 being most optimistic?

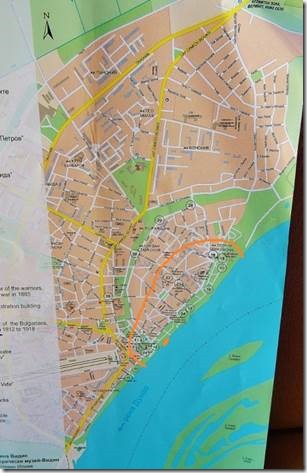

That’s not an easy question. There are different scenarios. In one scenario, Bulgaria’s future place would be 6-7. But in another scenario, I would evaluate it as 2-3. It depends on how the politicians cope with the situation. The main factor to support the positive evaluation is the European Union. I strongly hope that this current crisis will not lead to a terrible collapse of the EU. The EU is a disciplining factor for Bulgaria. The other factor for positive development is reforms in education. A lot of our children are now not compatible with the job market. The migration factor is also very important: young people are leaving Bulgaria. If we invest in people, young people will stay here and we’ll have a new generation of politicians and bureaucrats to rule this country. If this does not happen, then I’m afraid I’d give the lower grade. (In Silistra we were told by the young manager of the Hotel Dustra that many young people have left Silistra because they want better opportunities.)

Deep down in your heart, which scenario do you think is more likely?

Something in the middle. Democracy is already a norm in this country. It doesn’t function very well, but it doesn’t function very well anywhere in the world. I don’t think we’ll go downward; I don’t believe in the worst-case scenario. A lot of things have happened already in Bulgaria. Even if we have an authoritarian regime, which could happen, I’ll stick with 4.5

Do you remember where you were when you heard about the fall of the Berlin Wall, and what feeling you had, and whether you started thinking about its implications for Bulgaria?

I’d been in Leipzig, and I’d seen the large demonstrations there. I suddenly understood what “people” means. Until then, “people” was just something very abstract, like in the textbook. I saw those thousands of people on the square, and I was very enthusiastic. Later I learned about the fall of Todor Zhivkov on the train back to Bulgaria. In a way I expected it because I’d seen what was happening in Germany. It was an enormous joy.

At the end of 1989, everyone, even Communists, believed that something would change and we were going to another stage of our society. Unlike the Soviet Union, which had passed through glasnost and perestroika, the late 1980s were very hard for Bulgaria — like Romania where there was hunger and Ceausescu was totally mad. We didn’t have hunger like in Romania, but there were problems with electricity, with food. In Bulgaria, in the late 1980s, Zhivkov didn’t even pretend that he was making something like glasnost and perestroika.

The repressions were severe, starting with the so-called “Revival process.” One of the most important events in modern Bulgarian history was the forced re-naming of Bulgarian Muslims and Turks. This was the sign that this state was still totalitarian. The main thesis of this “Revival process” was that the ethnic Turks were Bulgarians who had been turned into Turks during Ottoman rule. That’s why the name “Revival” had been invented – as a return to their “true” identity. No one thought about how the ethnic Turks might feel about this in the 20th century. It was a terrible aggression against the very personality of these people. I call it “symbolic genocide,” an attempt to delete the names and identities of 800,000 people. I wonder how the people who carried out this “Revival” imagined that it could happen.

It was the late 1980s. Most Bulgarians, including me, didn’t understand what was happening. My son was born during that period, and I was busy taking care of him. The Communist Party started to understand that it’s not so easy to repress so many people. And the repressions started to grow. There was resistance, mostly carried out by ethnic Turks who resisted this renaming.

But some Bulgarians also started to talk about these issues in Sofia, in Plovdiv. Zheliu Zhelev’s book Fascism came out in 1982. No one can call this a dissident book now, but back then people treated it as a revolutionary act. The Communist Party and the Secret service were searching for signs of resistance and tried to control our minds all the time. But a new world had started to appear. It was mostly in people’s imaginations, and it was not so easy to control. We started to believe that we could live a different way. Everybody perceived this change in November 1989 as something that would change our lives, that would push society in a totally different direction.

It wasn’t expected. It was wanted, but it wasn’t expected. It was a very strange feeling. It wasn’t like Poland. In Poland they knew it would come since the early 1980s. But in Bulgaria, it wasn’t expected. Some people said that we should die with Todor Zhivkov in power and Lili Ivanova singing. I’m glad that Lili Ivanova is still singing, and Todor Zhivkov is no longer in power!

You mentioned that the path of development for the countries in the region was very different after 1989. I’m curious whether it pushed you personally onto a different trajectory.

Definitely. Actually, my career started after 1989. Before 1989, we had no freedom to write. When I was working at that institute for youth studies, our main job was to conduct research and write reports in a way that didn’t provoke the interest of functionaries in youth activities. We tried to present the situation as normal: yes, the youth have subcultures, but they’re not dangerous. This wasn’t real research. We had a lot of parties. We drank a lot. But we didn’t really work.

Only after 1989 did I understood what work meant. That’s when we started to make serious surveys and to write what we thought and not just cite party documents. That’s when we began to work for ourselves.

One of my favorite topics is what I call the “ideological construction of social status.” The Bulgarian Communist Party (BCP) manipulated status, because the salaries had been fixed according to the BCP vision about the priority of one branch over others and some occupations over others. My study showed that the most prestigious professions were low-paid, like doctors and teachers. The well-paid professions like those of construction workers and miners, had low prestige.

I did some sociological research on that. People knew that their salary didn’t depend on their effort. They worked, but they didn’t invest a lot of effort. In my research after the change, a lot of people told me, “Now we will work with pleasure, because we are working for ourselves. We will not depend on the state salary.” At the moment the opposite is happening — a lot of people are feeling nostalgic about the fixed salary, because there is a lot of unemployment and poverty. This means that something in the so-called “transition” went wrong.

Fortunately, this is not my case. I started to travel, go to conferences, meet people from different countries. The comparisons between countries were very interesting. Travel: that was one of the biggest changes. I can’t say that I was poor before the change. My family was part of the elite. I can’t complain about the conditions of my life. But what was lacking for me before 1989 was the feeling of freedom: to talk about what you think, to write what you think. Yes, after 1989 work became a pleasure for me.

You mentioned that your students have difficulty imagining what life what was like before 1989. Can you give me examples?

Take the example of the renaming of the ethnic Turks. When we had a meeting at the university, where party functionaries explained to us the “important” meaning of this process, the bravest thing some of the university professors had done was to ask a question: what’s happening? Why are you doing this? The students can’t imagine this. “Why didn’t you protest?” they ask. “Why didn’t you go out on the street?” They can’t imagine our fear and self-censorship.

They can’t understand that people were sent to labor camps because they had listened to Western music and dressed a different way. The situation here was not as bad as in the Soviet Union, but we had such camps, Belene being the most famous. The students can’t imagine that someone could be punished for dressing differently. They can’t understand the hidden, Aesopic language used in the works of artists and dissidents that was perceived by us, people who had “lived socialism,” as a kind of resistance.

There is a very good book by my colleague Pepka Boyadzhieva called Social Engineering – about higher education in Communist Bulgaria. She studied the papers written by the Fatherland Committees concerning the admission of students to higher education. There were sentences in those reports like: she has a “bourgeois look,” he has a “bourgeois gesture.” This is unimaginable even to me. How can someone decide if you should be a student or not because of your gestures? This was the late 1940s and early 1950s. After that, it was not so strict.

Do they see any relevance from that period of time to their lives today? Or is it just ancient history happening in a different country?

They cannot imagine this life, but at the same time — and we conducted research on this — they believe the family stories. Their perception of communism is mostly from these family stories. A lot of Bulgarians, mostly from villages and small towns, now have a growing nostalgia toward the Communist regime. It’s based on the memories of the security of their lives back then.

My son did some research on the memory of the renaming of ethnic Turks. Even some of those who suffered this humiliation remember with some nostalgia the security of life: “we had jobs then,” they remember, “We could go to the seaside then. Yes, we did not have lots of opportunities to travel and eat different types of food, but we had a calm life.” The following phrase had become a cliché: now there is everything in the shops and lots of opportunities, but we don’t have the money to take advantage of them, so we feel worse than in the Communist time.

So, yes, they can’t imagine that life. On the other hand, they have this quite simplified notion of communism presented to them by their grandfathers and mostly by their grandmothers, and probably by some of their parents. It’s true that Bulgaria went through a very heavy deindustrialization. A lot of people are not living so well right now. The bad things are forgotten. That’s normal from a psychological point of view. They’re forgetting the lack of freedom, the poor life, the long queues, seven-year wait to get a car. They just remember the security of yesterday compared to the insecurity of today.

You gave the mark of 10 when talking about your own personal life. But are you ever tempted by this kind of nostalgia?

No. I do insist that I had an excellent life before 1989 compared to the life of a lot of people. We lived really quite well. My father got good money. He was famous as an actor. I studied in good schools: due to my efforts, not due to my father. After the changes, some of my schoolmates said to me, “You can’t imagine how poor we felt compared to you.” That’s when I reflected on the inequalities under communism. I had a very good life before 1989 and I do not regret my life before the changes, but I do feel better now because of the feeling of freedom, how I feel about my work, the sense that something depends on me.

The number of young people leaving Bulgaria is quite large. Is it just a question of economic opportunity, or are there other factors behind people leaving?

One of the problems of the liberal model is that everything is calculated in money. Especially social scientists, in my field of sociology, believe that money is a very important push-pull factor. I don’t think this is so. Research shows that the people going abroad have middle status. It’s not the wealthiest or the poorest but, rather, the people who have a relatively good salary and even belong to prestigious professions. A lot of teachers, for instance, are going abroad; even ex-mayors have gone abroad.

My research is on temporary migrants. According to this research, it looks like people are going abroad in search of a better life but also to prove themselves. Bulgaria is too small to prove one’s self. They want to measure themselves in other countries, to try their strengths and capacities in different situations. This is their narrative. When I went abroad, I also rediscovered myself when I suddenly found that I could manage quite well. Young people are going abroad looking for better chances, better self-realization. Another important factor is that people want to live in a more regulated environment where the law means something and institutions work well.

Recently I found another motive among my students. They want to live in a more tolerant environment. I wonder whether Austria is really an example of tolerance, but my students feel that way. They want to live in a more multicultural environment. Bulgaria is very provincial. It’s like a small village where everyone knows everyone else, and different people are rejected. They want to live in a mixed and more colorful environment.

But Bulgaria is starting to open up to different people. And we will get used to living with different people. My son throws parties in the very small town where my grandmother’s house is located. He invites lots of friends. The noise is unbelievable until early morning. When I go to the town after these parties, I expect that I’ll get attacked because the party was very noisy, the neighbors couldn’t sleep. But they said, “No, no, it’s okay. It’s just young people. But Petya, do you know who they invited? A black man!” They saw face to face an African-American. So, you can imagine how closed this society was and still is. For people who are used to traveling, to going to different universities, Bulgaria now looks too white, filled with white people.

Tell me about the research you’re doing now.

I’ve just concluded some research on Roma integration. But that’s a long discussion. I dream of doing research on the children of temporary immigrants. Usually migration is viewed through the eyes of those who left rather than those who were left behind. I’ve found terrible cases of children who stayed here and made great efforts to attract the attention of parents who had gone to work for money in other countries. Those children stayed here, and some of them — or most of them, we don’t know how many — engaged in criminal acts. For me, it’s very interesting to look at the fates of these children. The striving for upward mobility, the attempt to make a career, often comes at the price of the downward mobility of your children. Here money is not the only thing. Caring for your children is also very important. I haven’t started this research because I haven’t found the money for it. But this is my dream.

I’ve done research on nationalism, attitudes toward Roma and foreigners, discrimination, migration issues. Before, I did social inequalities under communism and the memory of social inequality during communism.

I’m most interested in the studies on nationalism, discrimination, and attitudes toward Roma. But let’s start with your research on nationalism.

I was looking at the type of national identity Bulgarians have, whether ethnic or civic. So, I was looking at the feeling of nationalism versus the feeling of citizenship. Our education and the public debate should concentrate on civic national identity, on political national identity, on civic participation. Unfortunately, national identity for ethnic Bulgarians, not Turks or Roma, is built around ethnic identity — historical notions about our glorious past, which presupposes the enemies we fought against. It’s quite worrisome.

This has two important consequences. First, if you think of the nation only in ethnic terms, you exclude Roma, Turks and all the people coming here from other countries. In this multicultural environment, this is quite old-fashioned, and it could become dangerous.

Second, it’s commonly accepted by Bulgarians that our country is very beautiful but our state is corrupt and bad. I’m afraid there is some truth in this statement. But it is also dangerous. This belief that our state is nothing and should not be respected leads to people not wanting to participate in public life. They don’t think anything depends on them. If the state is corrupt, we should try to make a life only for ourselves and our family. There is a large disappointment in the functioning of democratic institutions. And when they think of Bulgarian statehood, they imagine the glorious state of the khans of the 9th century or the glorious dreams of the fighters for independent Bulgaria who wanted a strong and large Bulgaria.

This dream for the strong state is usually associated with a strong person. It worries me that the political is becoming more personified, that people are thinking about politics in terms of persons. This combination of ethnic nationalism and the desire for a strong state personified by a strong figure is not a good path for the future.

In Russian there are two words for Russian — russky and rossissky — to distinguish between ethnically Russian and Russian citizens. And in Bulgarian?

There’s just one word: Bulgarsko. Before, our politicians spoke in terms of “people.” Populism plays with this notion of people: ein volk, ein fuhrer. I do not accept the word “people.” There is no collective body. There are different persons, with different interests. In English, there is “we, the people,” and there is a feeling of diversity in “we.” In Bulgarian, like in German, there is no “we.” People are one collective body — narod.

Now our politicians are starting to use the term “citizens.” It’s a good sign. But I’m afraid that it’s a bit of a political manipulation to pretend that their parties are not parties but civic movements. Again it’s a matter of trying to convince us that they are representing all the citizens. So, the word “people” as in the “people’s republic of Bulgaria” has changed to: “we are working for you, all the citizens of Bulgaria.” In one way, it’s important to have this word “citizens.” On the other hand, it’s not good that citizens are thought of as one unity, not as different citizens.

It’s interesting that you say you don’t believe in “people.” But one of the first things you said is that after Leipzig, you understood for the first time what “people” meant and you were enthusiastic.

Yes, you’re right. You got me! Yes, I understood what “people” meant and I was enthusiastic about it. But I was also frightened. It means revolution. It means people coming together to destroy something. Revolution is a little bit dangerous. I’m more of a pacifist. I understood what “people” meant at that moment because before “people” was a cliché, an abstraction: all of us believing in the bright future of communism. Suddenly this abstraction came alive, all rejecting the communist “here and now.” Thousands of people shouting on the square “Wir sind das Volk” — Das Volk or Narod or the People – and acting as a fist is quite frightening. It’s preferable to have different groups with different interests with different religions, different skin colors, who can sit and talk together. I prefer differences that can be negotiated or at least debated. The essence of democracy is in this. We should try to resolve our differences by trying to understand each other.

I’m curious about the conclusions of the Roma and discrimination study.

A lot of what we found was evidence of racist attitudes. About one-third of respondents answered that they could not accept for a colleague or a boss a person of Roma origin or African-American origin. So, it’s not good. There are strong discriminatory attitudes toward Roma. But what is new is that Roma are now starting to be perceived as a privileged group, due to the fact that there is a lot of talk about strategies for Roma integration. That’s quite a paradox: for a vulnerable group to be perceived as a privileged group.

It is true, that there are a lot of public strategies about Roma integration, but nothing is happening. There are only words. At the moment any talk of affirmative action is not helpful. We should talk in terms of everybody having equal rights. This libertarian discourse is very useful here because Bulgarians do not believe that Roma are discriminated against in their normal lives, in their basic human rights – in employment, housing, health care. We should speak of ensuring a normal quality of life for poor people.

Usually Roma are associated with criminality. But people forget that organized crime, another hot issue, is the most important problem in Bulgaria. And organized crime is not related to Roma.

It’s a cliché to say that we should start to do something, not only to talk about things. But in a way, this is the case. I think we need to start with education. Roma children should be in the schools and they should receive a good education to overcome poverty.

Sofia, September 25, 2012 http://www.johnfeffer.com/remembering-the-calm-life/

|