Cheers,

A while back now, Randal and I joined a www.walks.com tour called The Blitz. 1n 1969 Randal was a Marine in Vietnam. I have never had to deal with the fears of war. While in Israel we did hear distant bombing, had bags searched in every place people congregated like malls and bus stations, and saw young members of the military with their rifles everywhere. But we weren’t afraid and really had no worries, especially, as had there been major troubles, we could have left it all behind.

In Sicily, in Palermo, bombed buildings are still visible. Most bomb damage here in London seems to have been rebuilt. Bits have been left as historical evidence such as melted lead in All Hallows Church or chips out of buildings. So for me, our blitz tour walk was an intellectual exercise not an emotional one. Everything we saw was rebuilt and shiny though not without controversy. If you are like me and have been lucky enough never to have had the experience of hearing bombs dropping on your home or as you walked through the streets, or have parents or grandparents who had to deal with it, then you can only be thankful. I don’t think you can really understand it. Pictures do tell a story though so I’ve taken some from various websites to post with this email.

Ru

|

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-12016916 http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/topics/christmas_in_world_war_two#p00cyd3y video clip about the saving of St Paul’s. http://www.thebeadlesoflondon.com/Pages/TheBeadleatWar.aspx interesting photos and story about people trying to save buildings in the area |

|

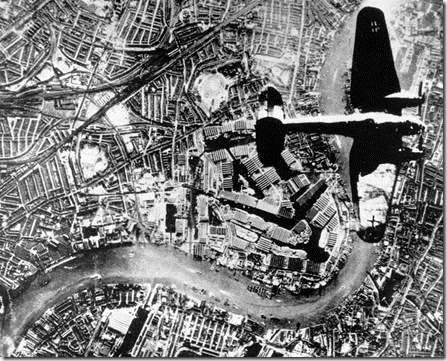

World War II in Photos A Retrospective in 20 parts “A Nazi Heinkel He 111 bomber flies over London in the autumn of 1940. The Thames River runs through the image. (AP Photo/British Official Photo) # “ |

|

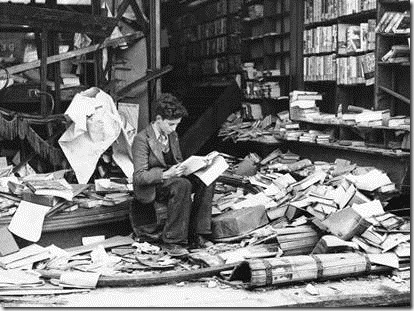

“A boy sits amid the ruins of a London bookshop following an air raid on October 8, 1940, reading a book titled "The History of London." (AP Photo) #” “In the summer and autumn of 1940, Germany’s Luftwaffe conducted thousands of bombing runs, attacking military and civilian targets across the United Kingdom. Hitler’s forces, in an attempt to achieve air superiority, were preparing for an invasion of Britain code-named "Operation Sea Lion." At first, they bombed only military and industrial targets. But after the Royal Air Force hit Berlin with retaliatory strikes in September, the Germans began bombing British civilian centers. Some 23,000 British civilians were killed between July and December 1940. Thousands of pilots and air crews engaged in battle in the skies above Britain, Germany, and the English Channel, each side losing more than 1,500 aircraft by the end of the year. Prime Minister Winston Churchill, speaking of the British pilots in an August speech, said, "Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few." The British defenses held, and Hitler quietly canceled Operation Sea Lion in October, though bombing raids continued long after. (This entry is Part 4 of a weekly 20-part retrospective of World War II) [45 photos]” |

|

Paternoster Square destroyed during the blitz SILVER GELATIN PRINT City bomb damage, Paternoster Square during the Blitz World War II bomb damage to the west side of Paternoster Square, looking towards St. Paul’s Cathedral, caused by the German bombing raid on the City of London on the night of 29 december 1940. Maker:Cross, Arthur (photographer); Tibbs, Fred (photographer) Production Date:1940-12-29 ID no:IN6898 – See more at: http://collections.museumoflondon.org.uk/ |

|

Virginia Woolf writes about her experience in the blitz Tuesday 10 September [1941] “Back from half a day in London – perhaps our strangest visit. Mecklenburgh Square roped off. Wardens there, not allowd in. The house about thirty yards from ours struck at one this morning by a bomb. Completely ruined. Another bomb in the Square still unexploded. We walked round the back. The house was still smouldering. That is a great pile of bricks. Underneath all the people who had gone down to their shelter. Scraps of cloth hanging to the bare walls at the side still standing. A looking glass I think swinging. Like a tooth knocked out – a clean cut. Our house undamaged. The garage man at the back – blear eyed and jerky – told us he had been blown out of his bed by the explosion; made to take shelter in a church. He said the Jerrys had been over for three nights trying to bomb King’s Cross. So we went on to Gray’s Inn. Left the car and saw Holborn. A vast gap at the top of Chancery Lane. Smoking still. Some great shop entirely destroyed: the hotel opposite like a shell. Heaps of blue green glass in the road at Chancery Lane. Men breaking off fragments left in the frames. Then to the New Statesman office: windows broken, but house untouched. We went over it. Deserted. Wet passages. Glass on stairs. Doors locked. So back to the car. A great block of traffic. The cinema behind Mme Tussaud’s torn open: the stage visible; some decoration swinging. All the Regent’s Park houses with broken windows, but undamaged. And then miles and miles of ordinary streets – all Bayswater – as usual. Streets empty. Faces set and eyes bleared. Then at Wimbledon a siren – people began running. We drove, through almost empty streets, as fast as possible. Horses taken out of the shafts. Cars pulled up. The people I think of now are the very grimy [Bloomsbury] lodging house keepers; with another night to face: old wretched women standing at their doors; dirty, miserable. Well – as Nessa said on the phone, it’s coming very near. Sunday 20 October [1941] The most – what? – impressive, no that’s not it – sight in London on Friday was the queue, mostly children with suitcases, outside Warren Street tube. This was about 11.30. We thought they were evacuees, waiting for a bus. But there they were, in a much longer line, with women, men, more bags and blankets, sitting still at 3. Lining up for the shelter in the night’s raid – which came of course. To Tavistock Square. With a sigh of relief saw a heap of ruins. Three houses, I should say, gone. Basement all rubble. Only relics an old basket chair (bought in Fitzroy Square days) and Penman’s board TO LET. Otherwise bricks and wood splinters. I could just see a piece of my studio wall standing: otherwise rubble where I wrote so many books. Open air where we sat so many nights, gave so many parties. So to Meck[lenburgh Square]. All again litter, glass, black soft dust, plaster and powder. Books all over dining room floor. Only the drawing room with windows almost whole. A wind blowing through. I began to hunt out diaries. What could we salvage in this little car? Darwin, and the silver, and some glass and china. Then lunch off tongue, in the drawing room. John came. I forgot The Voyage of the Beagle. No raid the whole day. So about 2.30 drove home. Cheered on the whole by London. Damage in Bloomsbury considerable. But miles and miles of Hyde Park and Queen’s Gate untouched. Now we seem quit of London. Exhilaration at losing possessions – save at times I want my books and chairs and carpets and beds – how I worked to buy them – one by one – And the pictures. But to be free of Meck. would now be a relief. But it’s odd – the relief at losing possessions. I should like to start life, in peace, almost bare – free to go anywhere. Virginia Woolf, Her Diary |

|

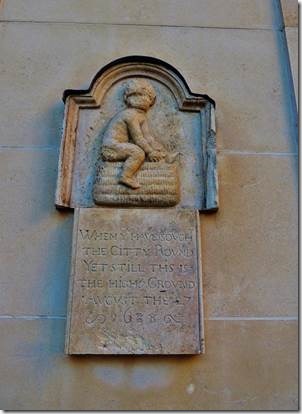

Our tour focused in the area around St Paul’s We met at the St Paul’s tube station. Just outside was this bas relief which has no connection to the Blitz but has an interesting story of its own. The Panyer Boy “ ‘When ye have sought the citty round yet this is still the highest ground.’ This alley was once the centre of London’s bakeries and said (wrongly) to be its highest point. This boy on his breadbasket has been hereabouts since 1688 and now sits just beside St Paul’s Tube Station.” Panyer Alley EC4 Tube: St Paul’s http://www.secret-london.co.uk/Other_Oddities.html “ Every informed source agrees that the bas-relief mounted on a wall in Panyer Alley is a cherished heirloom of the City of London. But there the concord ceases. The scale and scope of the disputes regarding the provenance and chronology of this simple stone tablet bear witness to the fog of uncertainty enshrouding much of London’s history before the better-documented 18th century.” http://hidden-london.com/the-guide/panyer-boy/ The link above explores all of the historic possibilities connected with the bas-relief illuminating briefly the problem of accurately writing history. |

|

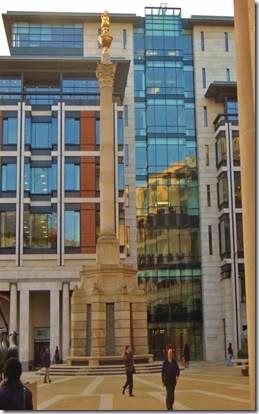

Blitz Tour From the www.walks.com link THE BLITZ – London at War "send every bloody pump you’ve got, the whole bloody world’s on fire" London Fireman during a Luftwaffe raid 8 September 1940 “The dome of St. Paul’s seemed to ride the sea of fire like a great ship. Ludgate Hill was carpeted in hosepipes. Two hundred people died that night. On the north side of the cathedral 63 acres became a waste of smoking ash and rubble. Another 100 acres were completely devastated in other raids that autumn. At the finish, out of the City’s tight-packed 461 acres, 164 were reduced to ruin. And this was just 1940.” From the walks website. As we huddled together on Ave Maria Lane in the afternoon cold, our guide gave us an overview of what life was like during the blitz. We were standing in an area that had been totally devastated, first by the Great Fire of 1666 and then by the blitz in 1940. It had been rebuilt in the 60s to popular disapproval. Proposals to again rebuild the area generated much controversy but in the early 21st century it was completed to divided acclaim and distain. Our guide seemed to think this current architecture was an improvement over the 60s design .. http://www.independent.co.uk criticizes the new architectural proposals. Wednesday 05 August 1992 http://www.architecture.com/ An architects defense of the new architecture |

|

This area was mostly destroyed during the Blitz…. Paternoster Square “One of the most exciting City developments, Paternoster Square, provides some 70,000m² of office space, retail outlets and cafes. The Square can trace its origins to medieval Paternoster Row, where the clergy of St Paul’s once walked holding their rosary beads and reciting the ‘Paternoster’, or Lord’s Prayer (Paternoster translates as ‘Our Father’). Soon, the area was a hub for peddlers of spiritual goods – such as rosaries and psalters (psalm books) – who relied on the passing trade of pilgrims visiting the old St Paul’s Cathedral. Mercers, stationers and lace-makers joined the mix, and the area remained a place of general business until the Great Fire of 1666. After the fire’s destruction of much of the surrounding property, the stationers returned, the publishers moved in, and the taverns and coffee houses (including the famous Chapter coffee house) that sprung up nearby, played host to many famous authors including Oliver Goldsmith, Thomas Chatterton and Charlotte Brontë. At the same time, the Square itself – a large open space – became the site of Newgate Meat Market, and remained so until the Central Meat Market at Smithfield opened in 1868. In the winter of 1940, St Paul’s was bombed and the area was destroyed for a second time (several million books were lost in one night when the booksellers’ shops came under fire). A modernist retail and office development rose up out of the ashes in the 1960s but soon fell out of popularity, with many of the units left vacant in the 1970s. A number of proposals to rebuild the Square were put forward and rejected. It was not until the Mitsubishi Estate Company commissioned Whitfield Partners in 1995 to create a master plan for a new development, which addressed both the heritage and the commercial requirements of the area, that redevelopment became a reality. The new development restores the lines of the ancient streets surrounding the Square and reclaims the public open space that is the Square itself. http://www.paternostersquare.info/about-paternoster.aspx Ave Maria Lane with views of St Pauls and Paternoster Column in the area as it looks today We walked from the tube station along Ave Maria Lane which opens onto Paternoster Square. “This area – originally Paternoster Row – resonates with the history of publishing houses and booksellers as, in the 1940’s; this was the centre of the British publishing trade. In December 1940, the entire area was devastated during the London Blitz – but miraculously St Paul’s Cathedral was saved. An estimated 5 million printed books were lost in the ferocious fires caused by the bombing.” http://eddieolliffe.wordpress.com/tag/paternoster-row/ The Paternoster Column “Whitfield Partners (architects) 2003, Portland stone, Cornish granite and gilded copper (urn) Situated at the focal point of the Square, the Paternoster Column stands 23.3m tall and is part of a ventilation system for the traffic gyratory and the car park beneath. The classic design follows an ancient tradition – stretching back as far as imperial Rome – of marking places of significance with monumental structures. Comprising a hexagonal stone base, a fluted Corinthian column and a gilded copper urn with flame finial, the column was designed to be the ‘centre of gravity’ for the entire Paternoster development, yet is deliberately not aligned on an axis with other architectural elements so as to create a ‘relaxed’ environment in the Square. The column itself is a recreation of those designed by Inigo Jones for the west portico of the old St Paul’s. Destroyed during the construction of Wren’s present day cathedral, replica columns of almost identical proportions and design can still be viewed at the west, north and south porticos. Running through the central service hole of the column are a lightening conductor and fibre optic cables for night-lighting of the urn, which was designed to provide a visual reference to a fire beacon, and thus fulfil the column’s purpose as a marker. The urn also reflects the finials on the west towers of today’s St Paul’s and commemorates the fact that the site has been destroyed twice by fire – the Great Fire of 1666 and the Blitz of WWII |

|

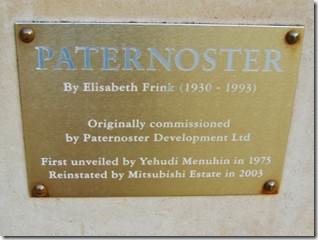

The Sheep & Shepherd Elisabeth Frink (1930–1993) 1975, bronze on Portland stone plinth Originally unveiled by Yehudi Menhuin in 1975, Frink’s sculpture stood at the centre of the north side of Paternoster Square until 1997 when it was moved to the Bastion High Walk (outside of the Museum of London) in advance of demolition work for the new development we see today. The work was reinstated to its present position in 2003. It is suggested that the sculpture was inspired by Frink’s stay in the mountainous region of Cervennes (France) where sheep and shepherds are a part of the everyday landscape, and by her admiration for Picasso’s 1944 bronze, Man with Sheep. The subject chosen may also have derived from a wilful confusion on Frink’s part between the pater of Paternoster (Our Father) and pastor (shepherd). Whatever the case, it is probable that Frink was not entirely free to choose and that influence was brought to bear, given the sculpture’s close proximity to St Paul’s. The evidence for this comes, not only from the religious connotations of the piece, but from the ‘androgynous’ looking shepherd and his flock – a characteristic not typical of Frink who was known for her well-endowed subjects. Originally commissioned by Paternoster Development Ltd; reinstated by Mitsubishi Estate Company in 2003. http://www.paternostersquare.info/about-paternoster.aspx |

|

CHAPTER XXIII. PATERNOSTER ROW. Its Successions of Traders—The House of Longman—Goldsmith at Fault—Tarleton, Actor, Host, and Wit—Ordinaries around St. Paul’s: their Rules and Customs—The "Castle"—"Dolly’s"—The "Chapter" and its Frequenters—Chatterton and Goldsmith—Dr. Buchan and his Prescriptions—Dr. Gower—Dr. Fordyce—The "Wittinagemot" at the "Chapter"—The "Printing Conger"—Mrs. Turner, the Poisoner—The Church of St. Michael "ad Bladum"—The Boy in Panier Alley. Paternoster Row, that crowded defile north of the Cathedral, lying between the old Grey Friars and the Blackfriars, was once entirely ecclesiastical in its character, and, according to Stow, was so called from the stationers and text-writers who dwelt there and sold religious and educational books, alphabets, paternosters, aves, creeds, and graces. It then became famous for its spurriers, and afterwards for eminent mercers, silkmen, and lacemen; so that the coaches of the "quality" often blocked up the whole street. After the fire these trades mostly removed to Bedford Street, King Street, and Henrietta Street, Covent Garden. In 1720 (says Strype) there were stationers and booksellers who came here in Queen Anne’s reign from Little Britain, and a good many tire-women, who sold commodes, top-knots, and other dressings for the female head. By degrees, however, learning ousted vanity, chattering died into studious silence, and the despots of literature ruled supreme. Many a groan has gone up from authors in this gloomy thoroughfare. One only, and that the most ancient, of the Paternoster Row book-firms, will our space permit us to chronicle. The house of Longman is part and parcel of the Row. ……….. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=45042#s2 |

|

“St. Paul’s Churchyard and Neighborhood (Note: This is taken from W. Roberts’ The Book-Hunter in London.) The bookselling and book-hunting annals of the district which starts with St. Paul’s, and terminates at Charing Cross, might occupy a goodly-sized volume……..” http://www.djmcadam.com/st-pauls-churchyard.html continues the story. |

|

Victorian London – Districts – Streets – Paternoster Row The Row, as it is called by way of pre-eminence, is the nucleus of the literary neighbourhood … How the literary man delights to haunt this place … He pauses, perhaps, before the immense emporium of the Longmans, with its fourteen windows in front, its little Ionic pilasters, and its iron crane, emblematic of the very heavy commodities in which the proprietors are sometimes compelled to deal. … Next to Longmans, the literary peripatetic will be attracted by the great extent of premises occupied by Whittaker and Co., extending half way down Ave-Maria Lane, and across to the neat but small quadrangle, with its solitary tree and little patch of grass, where the rich and influential Company of Stationers have their unpretending hall: the extensive mart for the lighter artillery of literature, under the control of Messrs Simpkin and Marshall, will also arrest his attention. The World of London, by John Murray, in Blackwoods Magazine, July 1841 http://www.victorianlondon.org/districts/paternoster.htm continues the story |

|

In the 16th century the neighbourhood was known for its many taverns. One of these, the Castle in Paternoster Row was kept by Richard Tarleton, the comedian who sometimes appeared at La Belle Sauvage in Ludgate Hill. The Chapter Coffee House, which later became the Old Chapter tavern, was also there. On occasions during the 1840s, while visiting the publishers Smith and Elder at their office at No. 65 Cornhill, Anne, Emily and Charlotte Brontë lodged at the Chapter Coffee House. Before The Great Fire of 1666, mercers, silkmen and lacemen also lived here. In fact, their products were in such demand by the well-to-do that the street was often jammed with their coaches. When the mercers moved out after The Great Fire of 1666, Paternoster Row became a centre for bookselling. In 1719, at the sign of the Ship, William Taylor published Robinson Crusoe. In 1724 Taylor’s business was purchased by Thomas Longman, founder of the Longman publishing company. http://www.ludgatecircus.com/paternoster_square.htm lots more information and historic maps here |