June 16, 2014

Deggendorf

Guten Abend

We scraped bottom once or twice today. The water level on the Danube is very low. There’s one more stretch up ahead that’s also shallow but hopefully it will rain here or the rising levels of water upstream from us will get here. As of tonight we’re planning to rent a car tomorrow to drive back and visit Walhalla, “ a white marble pseudo Grecian temple dedicated to the memory of famous Germans. Then on the 18th we’ll have to check the water levels again. Who’d a thought!

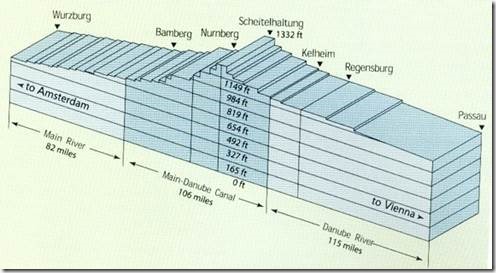

This email is about the Main-Danube Canal. I thought the 1930 Foreign Affairs article might add some interesting insights about the time. We encountered the biggest locks along the way; looked down on roadways below us; and crossed the “great divide.”

Ru

Locks Up and Down and Canal Over

Main-Danube-Canal · 2012

The Main-Danube-Canal, built from 1960 to 1992, is a 171 km long Federal Waterway Class Vb connecting the Main near Bamberg with the Donau at Kelheim. At the north ramp of the canal an altitude of 175 m is overcome by 11 locks and at the south ramp an altitude of 68 m is handled by 5 locks. The summit altitude between the locks Hilpoltstein and Bachhausen is 406 m above sea level, thus the highest canal reach in the European Waterway Network. Via the river Rhine, the canal enables a shipping connection between Rotterdam at the North Sea and the harbour of Constanta at the Black Sea.

The construction of the canal began in 1960 at the side of the river Main. The stretch between Bamberg and today’s port Bayernhafen Nuernberg was finished in 1972. Due to a catastrophic dam failure in 1979 at the following stretch between Nuernberg and Roth, resulting from a water flow round a pipeline in the dam, the further required dam stretches of the canal were placed as deep as possible and an excavated alignment was preferred.

In the 1970s and 1980s the construction of the south ramp of the canal between the locks Bachhausen and Kelheim was controversially disputed with respect to ecological, economical and safety-related aspects. Ecological objections refer especially to the alignment of the canal in the river stretch of the Altmuehl south of the lock Dietfurt down to the Danube. Up to the completion of the Main-Danube-Canal in 1992 the highest expenses for ecological compensatory measures have been spent in this stretch of the canal.

The locks of the Main-Danube-Canal have an effective length of 190 m, an effective width of 12.0 m and a vertical lift of 5.30 to 24.70 m. Most of the locks are shaft locks with economising basins. With a vertical lift of 24.70 m the identical locks Leerstetten, Eckersmuehlen and Hilpoltstein are the locks with the highest lift in Germany. The construction of the locks started in 1966 at the north ramp of the canal with the lock Bamberg and was finished with the lock Berching at the south ramp in 1991.

The main transported goods at the Main-Danube-Canal are food and feed followed by agricultural and forest products, ores and scrap, fertilizers, iron, steel and nonferrous metals as well as stones and soil. The total volume of goods transported on the Main-Danube-Canal in 2011 was 5.3 million tons after 6.2 million tons in 2010 (Traffic Report 2011, WSD Sued). In addition to the transportation of goods the passenger transport, both cruise vessels and day-trip vessels, play an important role on the Main-Danube-Canal with 180,000 passenger’s seats in 2011.

The video records of the locks Dietfurt, Kriegenbrunn and Hilpoltstein have been made by the Institute of Hydraulic and Coastal Engineering (IWA) of the Bremen University of Applied Science kindly supported by the Water and Shipping Authority Nuernberg. http://www.aquadot.de/videos/album-01-4/schleusen-e.html

|

In Bischberg we bought our new “bridge height pole” to make sure we can fit underneath. |

|

Our lock escort….. We followed ‘Constellation 1 of Wurzburg’ through all of the locks between Bischberg and Nuremberg. The captain was really courteous and warned us of low bridges and apologized for a short stop he had to make for a delivery. When leaving the locks he waited until he was far enough ahead of us to turn up his engines so not to churn up the water behind. |

|

June 10th Bischberg to Nuremberg The canal was built over roads and you look down on rooftops. |

|

A solar energy farm |

|

June 12th between Nuremberg and Berching 24.7 Meters and first floating bollard. |

|

The bollard slides so once you’re hooked on, that’s it. So much easier. I tried my hand at these and now Mary and I take turns. We were still going up river at this lock. The old fashioned bollards that meant changing at least a dozen times while you rose. The sliding bollard eliminates the need for these, but were only on one side of the lock. Sometimes the sliding bollard was on the east side and some on the west so you had to be prepared for either. We have 2 really big, heavy fenders bow and stern. They need to be on the side we’re tied up to. That means changing them depending whether the sliding bollard is on the east or west wall. With sliding bollards there’s time for boat work. Arriving at the top Looking back down the river at a ship waiting for the lock to recycle. |

|

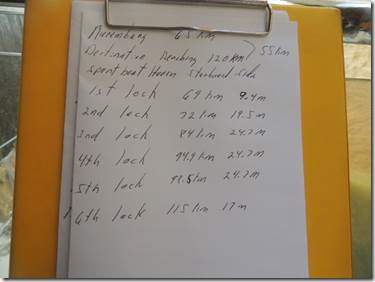

Keeping track of the locks and their heights. 24.7 were the biggest and thankfully had floating bollards. The final lock we went to down as we’d “crossed the divide.” |

|

The “divide” wall. Our first “going down” lock. |

|

http://www.foreignaffairs.com/ The Rhine-Danube Canal By Anonymous From our April 1930 Issue A CONSTANTLY navigable waterway through the heart of Europe, from the North Sea to the Black Sea, is now being constructed. Twice before it has been attempted. More than a thousand years ago Charlemagne tried to join together two tributaries of the Danube and Main Rivers, but geological conditions and heavy rains defeated his engineers. Nearly a century ago Ludwig I of Bavaria built a canal connecting the Main below Bamberg with the Danube at Kelheim. But this 107-mile canal, with its 100 locks and its capacity limited to 120-ton ships, went down to defeat before its latest competitor, the railroad; for while the upper reaches of the Danube and the Main are not always navigable, steam power is always on tap. And so the traveler through Nürnberg today sees from the train a deserted waterway. Determined to overcome the obstacles that were fatal to their predecessors, twentieth century engineers plan to make use of the 388 miles of navigable river from Rotterdam to Aschaffenburg and of the 1,362 miles of the navigable Danube from Sulina to Passau, and to construct from Aschaffenburg on the Main to Passau on the Danube — a distance of 380 miles — a waterway navigable for 1,500-ton ships (i.e., the largest ships usually engaged in inland traffic). They will also give Augsburg and Munich shipping connections with the canal. By a treaty signed in 1921 the German Government and Bavaria agreed jointly to construct a Rhine-Main-Danube waterway. The Rhine-Main-Danube Company, of Munich, was formed for the purpose, and the stock was subscribed to by the Reich and Bavaria, as well as by other German states, by cities along the Rhine and Main, and by the public; all loans to the company are jointly guaranteed by the Reich and the Bavarian Government. The American public is interested in the company to the extent of about $6,000,000. As the Main had already been canalized as far up as Aschaffenburg, the company first set out to canalize the river above Aschaffenburg and to regulate the Danube, so that these two stretches of river will be constantly navigable. When this work is completed, it will be necessary to cut a canal connecting the two rivers, and it is planned to merge into the new waterway parts of the Ludwig Canal, which is being considerably widened and deepened to meet the demands of twentieth century river traffic. A channel with a minimum depth of six feet has already been completed for a distance of 100 miles above Passau, and a dam and double locks have been constructed at Kachlet. Canalization of the Main above Aschaffenburg is proceeding rapidly; a dam at Obernau, about six miles above Aschaffenburg, is already in operation, and three others, at Kleinwallstadt, Klingenberg and Kleinheubach, are now under construction. In order to pass over the range of mountains separating the Main valley from the Danube, the waterway will have to accomplish a rise of nearly 1,000 feet from Aschaffenburg to the summit level, near Hilpoltstein, and then descend about 400 feet to Passau. This will be done by constructing 52 dams, and the locks will be so placed that ships will be able to proceed in the canal at an average speed of six miles per hour. In order to be assured of sufficient water for working the locks of this canal, a reservoir will be constructed at Hilpoltstein, to be fed by a canal about 45 miles long, which, crossing the Danube by aqueduct, will tap the River Lech below Augsburg. From the financial point of view probably the most valuable asset of the canal is the hydroelectric power stations to be erected at 38 of the 52 dams. It is estimated that the profits derived from the sale of power will within twenty-five years pay off the construction costs of each plant, and thereafter will contribute annually to the amortization of the capital invested in the waterway itself. When all the power plants are in operation, they are expected to yield 1,475,000,000 kilowatt hours annually. The Kachlet plant, above Passau, consists of eight 8,000-horsepower turbines with an annual capacity of 275,000,000 kilowatt hours; this electrical energy is carried by cables to Nürnberg and Furth. Each of the four power plants on the Main, mentioned above, has two turbines yielding between 18,000,000 and 22,000,000 kilowatt hours annually. With such a great source of electrical energy, Middle Germany, though far from good coal supplies, will soon enjoy plenty of power for her metallurgical and electro-chemical industries, and also for other industries and perhaps even for her railroads. Abundant electricity for industry will doubtless create new values for Austria also. The total cost of constructing the waterway has been estimated at $185,000,000, and the annual operation and maintenance cost are put at $800,000. But as sections of the waterway are completed, they may (at the request either of the Reich or of the company) be taken over by the Reich, in which event the company will be relieved of operation and maintenance costs. The cost of constructing the power plants (which will pay operation and maintenance costs out of profits from the sale of power) is estimated at $70,000,000. They are to be operated by the company until the end of the year 2050, when they revert to the Reich without compensation. The present program of work calls for an expenditure of $32,500,000, nearly half of which is to be contributed by the Reich in ten annual instalments. This trans-Europe waterway, with its western depot at London and its eastern depot at Sulina, at the mouth of the Danube, where freight can be transshipped for Russian, Turkish and Levantine ports, will be open to free competition to all countries. The Versailles Treaty declared the Danube international below Ulm (Art. 331), as also — were it ever constructed — the deep-draught Rhine-Danube navigable waterway (Arts. 331, 353); it also provided for "the free navigation of vessels and crews of all nations on the Rhine" (Art. 356). The Danube is administered by two international commissions. Traffic on the Danube has never equalled that on the Rhine, which passes through districts much more highly developed industrially. But since the war the Danube has become much more important as an international highway. Seven independent states now have access to its waters, five of them possessing territory on both banks. For Austria, Czechoslovakia and Hungary it affords the only practicable and independent right of access to the sea. It has been estimated that the canal connecting the Rhine and the Danube would attract at least 10,000,000 tons of shipping annually. To handle this volume of traffic harbors must be extended and improved, warehouses and docks must be built, and railroad and trucking services must be improved. Czechoslovakia already possesses, at Bratislava (Pressburg), big modern docks, and Aschaffenburg and Budapest have considerable harbors. Passau and Regensburg are looking forward to enlarging their docks, and ports in Jugoslavia, Bulgaria and Rumania are planning improved accommodations. The districts through which the canal will pass are mainly agricultural; but iron-ore deposits have been located in the highlands between Nürnberg, Bamberg and Baireuth, and the huge hydroelectric plants should, by encouraging the development of industry here, provide much traffic for the new waterway. Experts calculate that 48 percent of the total traffic on the new waterway will move westwards and 52 percent, eastwards. Germany will send to the Danubian states Westphalian coal, agricultural machines and artificial fertilizers (for both of which there is a great demand in the agricultural states of the lower Danube basin), as well as other finished products of her industries; in return she will receive agricultural products, timber and oil. Hungary, Jugoslavia and Bulgaria will benefit by the cheaper rates of water transportation for sending their surplus grain up the river to Czechoslovakia and southern Germany. Before the war, the regions now contained in Czechoslovakia produced about 75 percent of the industrial output of Austria-Hungary; this must now be exported, and, as Germany offers no market, it should logically be sold in Hungary and the other Danubian states, rather than as now in countries far distant, often overseas. But important as the waterway undoubtedly will be to the Danubian states, they will not benefit from it alone. France is interested in it because, in Alsace, she is again on the Rhine. Great Britain is interested, because of the possibilities it opens for the Levant trade and also for direct communication with the petroleum depots of Batum and Baku. Germany is interested, because she desires to revive her trade routes to the East, which is rich in raw materials. Ultimately, the waterway is of world importance, as affording a direct connection between the terminals of transatlantic shipping and the ports of the Levant. |