Novi Sad Marina

Здраво zdravo = hello in Serbian as we’re back in Serbia having spent the past 2 nights on the southwest bank of the Danube in Vukovar, Croatia. Very sad history in both Vukovar and Novi Sad during the 90s when the Serbs bombed the Croatians and the UN bombed the Serbs. It would take many hours to begin to understand the histories of these two countries. I’m sure your local library has books if you want to pursue it. Now in the heat of summer everyone just wants to fish, swim and eat ice cream… on both sides of the river.

This email tells about our tour of the Jewish Quarter in Budapest. Rick and Mary had visited the synagogue when they were here a few years ago so just Randal and I did the tour. Very interesting but the “Basic tour” was a bit too rushed. As well as researching what we did see, I’ve gone off on tangents (yet again) making this a quite lengthy email. Sorry.

Ru

“Budapest has the largest Jewish community in Central Europe with an active religious, artistic and historical Jewish heritage. Through the centuries the Hungarian and Jewish history has been intertwined. Hungarian Jews have always been and still are a significant part of the country’s economic, cultural, and political life.” Hungarian Koncert brochure

|

Ticket booth for walking tour information. Something in my history makes me not the least surprised how that sign is written. Seinfeld could probably have a field day with it. Waiting for the tour to being : Our snack to hold us over until a late lunch after the tour. So much sugar it set my teeth on edge. There was chocolate on the sides and bottom making it taste like a combination of a Snickers bar and baklavah so you can imagine! Randal and I shared it and each of us had a “large coffee” that was rather miniscule in my opinion. |

|

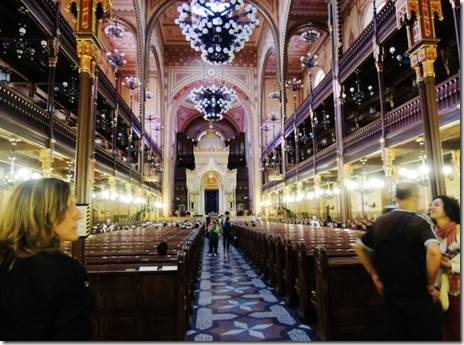

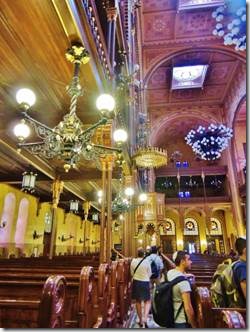

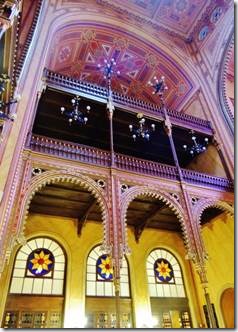

Dohany Street Great Synagogue with visitors from around the world. “Among Budapest’s trendy bistros, cafes and bars stands the world’s second largest synagogue. Like the Lower East Side of Manhattan or the East End of London, urban gentrification has had its way with Budapest’s District VII, transforming the once run-down area into a neighborhood of pricey coffees and young artists whose signature works appear to be their hair. Yet despite the neighborhood’s profound changes, one rare constant has remained: the 154-year-old Dohány Street Synagogue. The magnificent temple is the biggest in Europe and has touched the lives of figures as seemingly disparate as Estée Lauder, the cosmetics queen; Theodor Herzl, the father of the Zionist project that culminated in the State of Israel; and Tony Curtis, the Hollywood star. Dohány Street is located just east of the river Danube in the heart of Budapest. Appropriately, given the synagogue’s oriental style, the word Dohány, which means “tobacco,” made its way to the Hungarian capital from Arabic by way of Turkish. At the time the synagogue was built in 1859, the street was in the main Jewish area of Pest. Then there may have been as many as 45,000 Jews in the city. There was certainly sufficient demand for the synagogue to accommodate almost 3,000 worshippers—1,492 men in its main section and 1,472 women in the elevated galleries. Designed by the Viennese architect Ludwig Förster, the synagogue is over 75 meters long and more than 25 meters wide. Believing that there was no indigenous European Jewish architectural heritage, Förster looked to Arab architecture for inspiration. He primarily employed a Moorish revivalist style, of which the shul is considered a fine example, while he also incorporated Byzantine, Romantic, and Gothic elements. Perhaps the synagogue’s most distinctive feature is its onion-shaped domes with gilded ornament. They contribute greatly to the building’s oriental, Moorish look. Förster used similar domes on his design of the Leopoldstädter Tempel in Vienna, which was completed the year before the Dohány Street shul. The feature was subsequently copied on many other synagogues across Europe, including the much-visited Spanish Synagogue in Prague. In 1860, a year after the shul opened to the public, Theodor Herzl was born in an adjoining apartment building. Although (or perhaps because) he spent his early days next to the temple, Herzl has little interest in religion and considered himself atheist. Despite his atheism, Herzl became convinced that Jewish assimilation was doomed to failure while covering the Dreyfus trial as a journalist and also noting the anti-Semitic populism of the mayor of Vienna, Karl Lueger. His response was to launch formal political Zionism in 1897, and 51 years later the Jewish state was born. A plaque at the synagogue in Hungarian, English and Hebrew marks Herzl’s birthplace and his family’s former home became a Jewish Museum incorporated into the main Dohány Street Synagogue complex in 1930. History weighs heavily at the synagogue complex, which includes other commemorations of events that affected the shul and its community. A sculpture of a weeping willow tree represents the suffering Hungarian Jews endured at this site during World War Two; each leaf on every branch bears the name of a survivor’s relative murdered in the Holocaust. Of course the Shoah was the most seismic event in the history of the shul and its congregants. German troops invaded Hungary in March 1944 and the Nazi occupation of Hungary had immediate, devastating results. In April and May, Jews in the Hungarian provinces were ghettoized. Between May 15 and July 8, 437,402 Hungarian Jews outside of Budapest were sent to concentration camps, primarily Auschwitz. Nowhere was the pace of the destruction of Jewry as quick as in Hungary. Jews in Budapest faced severe antisemitism and Hungarian authorities ordered them into over 2,000 designated buildings marked with Stars of David scattered throughout the city in June 1944. But for a short time they were insulated from ghettoization and systematic deportations afflicting other Hungarian Jews. Nevertheless, Adolph Eichmann designated the synagogue as a concentration point from which to send thousands of Budapest’s Jews to their extermination. Many died from hunger, cold or disease before they even left the grounds of the synagogue. A small cemetery was built in a garden inside the grounds of the shul to bury some of those who perished during the time of the ghetto. More 2,000 are buried there. In October 1944, when it appeared that the war was almost over, with Germany close to defeat and Hungary about to proclaim peace with allies, the Arrow Cross, a pro-Nazi Hungarian fascist party, staged a coup d’état. The Arrow Cross forced the Jews of Budapest into a ghetto around the Dohány Street Synagogue in November 1944. Deportations started almost immediately after the establishment of the ghetto. In less than three months of existence, over half of the ghetto’s inhabitants were sent to concentration camps. The Hungarian fascists perpetrated a bloodbath in Budapest itself. Between December 1944 and the end of January 1945, they took as many as 20,000 Jews from the ghetto, shot them along the banks of the Danube, and threw their bodies into the river. To save bullets, the Arrow Cross only shot every other Jew; the others they threw in alive. From German occupation in March 1944 to Hungary’s liberation in January 1945, the Jewish population of Budapest was reduced from approximately 200,000 to 100,000. Yet compared to other European towns and cities, the community had got off lightly. While the sculpture of a weeping willow serves as a somber reminder of these events, the tree’s branches form an upside down menorah to symbolize hope and Jewish continuity. And alongside the upsetting, the synagogue complex houses a memorial to more uplifting stories: those who helped to ensure Jewish life in Hungary by saving Jews from the Nazis and their Hungarian cronies. In a cobble stone courtyard, stone tablets honor righteous gentiles in a similar, albeit smaller, fashion to at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem. The first and best-known name on the list is Raoul Wallenberg. A Swedish diplomat, Wallenberg saved the lives of thousands of Jews in Budapest by providing them with fake passports or shelter at hospitals under the protection of the Red Cross. Wallenberg and other diplomats from neutral countries saved the lives of tens of thousands of Hungarian Jews. He is one of the more than 600 Hungarians registered as righteous gentiles at Yad Vashem. The synagogue was damaged in air strikes during the liberation of Budapest but after the war it became once more a major congregation point for surviving Hungarian Jews. But following the fall of Nazi Germany, Soviet troops occupied Hungary and the country gradually became a communist satellite state of the Soviet Union in which religion was repressed. As the years went by the once-magnificent Dohány Street Synagogue fell into disrepair. As communism fell, interest in the synagogue rose. Private donors paid to restore it to its former glories. They included Estée Lauder and Tony Curtis, who were both born to Hungarian Jewish parents in New York City, and Curtis’ daughter Jamie Lee Curtis. But this was not the first time the shul had attracted stars: the major Hungarian composer Franz Liszt played its 5,000 pipe organ back in the 19th century. In the 1990s, thanks to the beneficence of those moved by its beauty and history, the Dohány Street Synagogue was reconstructed according to its original designs. It now looks identical to when it was first built. Today as before, the temple serves as the religious center of the Budapest Jewish community, which is one of Europe’s largest. In 2010, the demographer Sergio Della Pergola estimated that there was a core Jewish population of 48,600 in Hungary, the vast majority of which lives in the capital. The synagogue has 28 Torah scrolls—all of which survived World War Two, when two priests hid them in a Catholic seminary—and it is packed on high holy days. As well as housing the Jewish Museum, the shul is also a cultural center, with concerts taking place throughout the year. Now locals and tourists from around the world can once again enjoy the synagogue’s internal frescoes, its beautiful, ornate stained glass windows, and its bold, yellow and red Moorish exterior. The shul is not only the second largest in the world; it is one of its most glorious. Perhaps it is fitting that the synagogue is known throughout the world because, in a way, the State of Israel was born by the Dohány Street Synagogue. At least Theodor Herzl, the man credited with its founding, certainly was, and the shul’s influence has traveled far beyond the boundaries of Budapest’s District VII. In fact, if Budapest is too much of a schlep and New York City is closer to home, you can see the impact of the Dohány Street Synagogue at East 55th Street and Lexington Avenue. There you’ll find New York’s Central Synagogue, which is a near-exact copy of the Dohány Street temple; a replica of East-Central Europe in Midtown East. All that’s missing is the trendy bistros, cafes and bars. . |

|

Mix a “world weary” Brooklyn Jew now living most of the time in Israel and you get our guide. Only time I saw him show any emotion was an exchange he and I had about the Red Sox and Yankees. He did make a funny comment that half of us were on the tour because if we hadn’t gone we would get home and hear,” You were in Budapest and you DIDN’T GO TO THE SYNAGOAGU!!!!” I have to say, that’s part of the reason I was there. However, both of our Budapest walking tour guides mentioned the Jewish quarter and the Dohany Street Great Synagogue, making it a tourist destination for everyone. Our guide also said that most people think the synagogue looks more like a church and I think I’m in that group. The synagogue was built in the style of the time to fit in. And it needed to be huge to accommodate all of the congregants. Now they use loud speakers when the thousands of people come for Yom Kippur and want to hear the Kol Nidre chanted. Also, the congregation was Neolog which is a sort of Conservativism but definitely not Orthodox and not Reform either. It seems a form of Judiasm peculiar to Europe. We were also told that I Nazi flag was placed atop the building by Eichman (who used the synagogue as an office) so as not to be bombed by the Germans. The flag was left up so when the Russians arrive, the building would be bombed by the Allies. Thankfully something added atop the building..can’t remember exactly… saved the synagogue from distruction |

|

What are these mid-synagogue pulpits for? Our guide explained that they are atypical for synagogues but because one comes to hear as well as participate, these were needed so readers could be heard throughtout the building, downstairs and up in the two-level balcony. If I remember correctly we were told that men and women sat together except on high holidays…but don’t quote me. Randal wanted a photo of the ceiling supporting the lower balcony as future reference for our someday house. |

|

Past members killed during the Holocaust are remembered by name plates. |

|

Somewhere there is an organ, but I didn’t see any pipes. The building to the left of the synagogue is the Herzl’s home, now a museum. |

|

The buildings and the courtyards of the Synagogue include the Jewish Museum, the Heroes’ Temple, the Jewish Cemetery and the Raoul Wallenberg Memorial Park. Jewish Museum – The Jewish Museum was constructed on the site where Theodor Herzl’s house once stood. The Museum is adjacent to the Great Synagogue, and it features Jewish traditions, costumes, as well a detailed history of Hungarian Jews, including information about the Holocaust. Jewish Cemetery – The cemetery is located in the backyard of the Heroes’ Temple. There are over 2,000 people buried here who died in the Jewish ghetto during the winter of 1944-45. Raul Wallenberg Memorial Park – The Raul Wallenberg Memorial Park, home to the Holocaust Memorial, is located in the backyard of the Great Synagogue. The Holocaust Memorial, also known as the Emanuel Tree, is a weeping willow tree (by Imre Varga) with the names of Hungarian Jews killed during the Holocaust inscribed on each leaf. The memorial was sponsored by the Emanuel Foundation of New York. The foundation was created in 1987 by Tony Curtis in honor of his father, Emanuel Schwartz, who emigrated to New York from Mátészalka in Hungary. Heroes’ Temple – The Heroes’ Temple was added to the Great synagogue in 1931, and it serves as a memorial to Hungarian Jews who gave their lives during World War I. Also part of the memorial are four red marble plates, commemorating 240 non-Jewish Hungarians who saved Jews during the Holocaust. One of the most heroic figures of the Holocaust in Hungary was Raoul Wallenberg, a Swedish diplomat who prepared Protective Passports under the authority of the Swedish Embassy, saving the lives of thousands of Jews. http://visitbudapest.travel/guide/budapest-attractions/great-synagogue/ “Wallenberg saved tens of thousands of Hungarian Jews from the Nazis by issuing them with Swedish papers during 1944-45, only to then disappear in Soviet custody after the war.” |

|

Our guide was very sweet, but her microphone didn’t work well and half of the group couldn’t hear. Plus she had to talk fast to get most of the group back to the synagogue for the 1:30 tour. |

|

Rumbach Street Synagogue, The Scarlet Pimpernel, Leslie Howard, and Raoul Wallenberg…. “The synagogue was designed by the most renown Viennese architect of the late 19th-early 20th century, Otto Wagner, the creator of architectural modernism. It was built between 1868 and 1872. The building is the most stunning example of arabesque synagogues around the world, with probably the nicest inner space amongst the synagogues of Budapest. The earlier, smaller temples of Budapest’s Jewry were situated in the court of the Orczy-House, a conglomerate of many buildings on the corner of Király utca and Károly körút. The building was rented to the Jews by the Orczy barons before 1840, when royal cities prohibited their settlement. After 1840 the parliament permitted Jews to acquire real estate and the Jews in Budapest soon intended to erect a Synagogue on a separate piece of land (…) Prayers were held in the Rumbach Street Synagogue until 1959. At the end of the 80’s, a construction company bought the property and decided to completely restore it, then to sell the building. This restoration was carried out only to some degree, however; the street façade and the structure of the synagogue were refurbished and the cover of the inner walls was redone. In 1992 the company went bankrupt and in exchange for its liabilities, the building was handed over to the Hungarian Privatization and State Holding Company (ÁPV), from where it was returned to the Budapest Jewish Community.” http://zsidonyarifesztival.hu/rumbach-utcai-zsinagoga/?lang=en The name Orczy rang a bell to me. In junior high I read the book The Scarlet Pimpernel by Baroness Orczy. My copy had an image of a pimpernel so I was allowed to read it. My friend Bruce’s copy had sort of a bodice ripper cover : back in 1962ish this was risque so he was told he couldn’t read it. I can’t remember the exact outcome, but I remember totally enjoying the book. I recently tried to watch some Youtube shows of Anthony Andrews as The Pimpernel but it was too awful. “Baroness Emma Magdolna Rozália Mária Jozefa Borbála “Emmuska” Orczy de Orczi was born in Hungary in 1865. Her family moved to England when she was 15. She later married Englishman Montague MacLean Barstow. Baroness Orczy is best known for her book, The Scarlet Pimpernel.” http://becomingemily.wordpress.com/ In 1934 the book was made into a movie starring Leslie Howard. Howard then produced, directed and was the lead actor in an updated Pimpernel movie in 1941 called Pimpernel Smith. Pimpernel Smith : Having saved a good many heads from the French revolutionary guillotine in the film of a few years back, the Scarlet Pimpernel is back in a new disguise. "Mister V" is what he calls himself in the new arrival at the Rivoli, and this time he is a crotchety, vacant-minded archaeologist smuggling deserving souls out of the reach of the Nazi terror. Out of his adventures amid the gutterals and brown shirts, Leslie Howard as producer, director and leading player has created an uneven but decidedly exciting melodrama. Perhaps Mister V’s exploits sometimes have a familiar ring, No matter, "Mister V" is still a pulse-quickening variation on a dangerous theme. Singapore may fall, but the British can still make melodramas to chill the veins. http://www.nytimes.com And all of this is connected to Raoul Wallenberg. “And it was a British wartime propaganda film, Pimpernel Smith, which gave Mrs Lagergren her first inkling that Raoul would do something special. The film takes the action of the Scarlet Pimpernel into pre-war Nazi Germany, telling the story of Horatio Smith, a British archaeologist trying to save inmates of concentration camps. “They couldn’t show it openly in Stockholm, because it was anti-German. So they had a special cinema where we could see it, specially invited, at the British embassy. This was in 1942. And afterwards Raoul said: that is something I would like to do. ..” http://www.raoulwallenberg.net/ |

|

http://www.rumbachstreetsynagogue.hu/ The ark doors to the left of the photo showing how the synagogue once looked. Words to definitely live by; for anyone of any religion. The building was open because to set up for a concert, or take down from a concert… so we could go inside. |

|

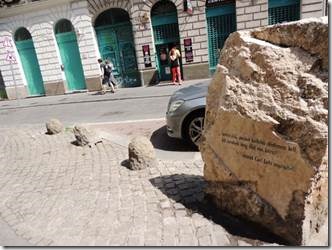

Stumbling stones are embedded in Bucharest also http://topbudapest.org/budapest-stumbling-stones first stones were laid in 2007 |

|

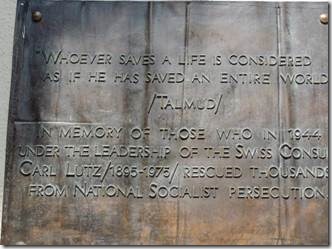

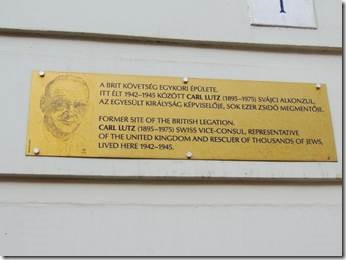

Carl Lutz memorial in the Jewish Quarter. The American Embassy also has a memorial. I knew about Raoul Wallenberg but not about Carl Lutz “Whoever saves a life is considered as if he has saved an entire world.” Talmudic saying. During the war, Swiss diplomat Carl Lutz (1895-1975) helped save tens of thousands of Jews in Budapest from persecution and deportation. Located on the area of the former Budapest ghetto is a monument dedicated to his memory. “Neutral Switzerland represented the interests of citizens from several states which had since 1941 been at war with Hungary, including Great Britain and the United States. From the beginning of 1942 on, Carl Lutz led a special department for the protection of these citizens as vice-consul at the Swiss embassy in Budapest. Deliberately exceeding his authority, Lutz issued tens of thousands of Jews protective letters, which were to shield them from deportation and persecution. Moreover, he was involved in helping Jews emigrate to Palestine, which was at the time under British mandate. Lutz closely worked together with the Zionist »Jewish Agency for Palestine«, led by Moshe (Miklós) Krausz. This organisation was responsible for distributing emigration papers for Palestine. When the German Wehrmacht invaded Hungary on March 19, 1944, Lutz placed the »Jewish Agency« under the protection of the Swiss embassy. The Agency moved into the »Glass House« in Vadász Street 29. Lutz and his helpers did all they could in order to issue as many so-called protective letters and protective passports as they could. Carl Lutz took advantage of the fact that the Hungarian government had – due to pressure from abroad – agreed to allow 8,000 children and youths to emigrate to Palestine, and that these had been in possession of Swiss documents before the German invasion. Lutz and Krausz interpreted the decree to mean that not only individuals holding these documents but their entire families would be allowed to emigrate, thereby placing tens of thousands of people under their protection. After the establishment of the Budapest ghetto in the winter of 1944, Lutz established numerous »safe houses« under Swiss protection and tried to arrange the best possible conditions for the Jews who sought refuge there. About 119,000 Jews were liberated in Budapest when the Soviet army took the city. It is neither known nor possible to determine how many were saved due to the efforts made by Carl Lutz. Several sources speak of up to 62,000 lives saved. For a long time after World War II, the deeds of Carl Lutz were forgotten. His reception in Switzerland was more than cool; he was accused of having exceeded his authority as a diplomat. In 1965, Yad Vashem awarded him the medal of the »Righteous Among the Nations«. The monument by sculptor Tamás Szabó was set up in 1991 in direct vicinity of one of the former entrances to the Budapest ghetto. “ http://www.memorialmuseums.org/ Another memorial plaque in another part of Budapest outside the Jewish Quarter |

|

The still functioning Kazinczy Street orthodox synagogue “In 1997, the Jewish community of Miskolc numbered some 250 aged survivors of the Holocaust. According Mr. Birnbaum, then the shammas of the Kazinczy Utca synagogue, about 24 people came to services each Shabbat. These congregants were far too poor to see to the upkeep of the synagogue, which was sadly neglected and in disrepair. Even so, one could see that in its heyday, the synagogue must have been glorious. When a visitor remarked upon the beauty of the chapel, the elderly shammas replied, "It was beautiful when it was full." Few words could memorialize more exquisitely and succinctly the thousands of Miskolc martyrs of the Holocaust” http://kehilalinks.jewishgen.org/miskolc/synagogue-2.html “The most significant cultural sight is the Kazinczy Street Orthodox Synagogue, located around the middle of the street at No. 29-31. The synagogue is attended by Budapest’s orthodox Jewish community. The neo-renaissance building was finished in 1912 according to the design of the Löffler brothers. The traceries, hand-painted by Miksa Róth stained glass artist are beautiful ornamental elements of the Kazinczy synagogue. http://www.budapestbylocals.com/kazinczy-street.html http://www.budapestarchitect.com/ discusses the brothers and their architecture. This is a really good website about Budapest architecture in general. |

|

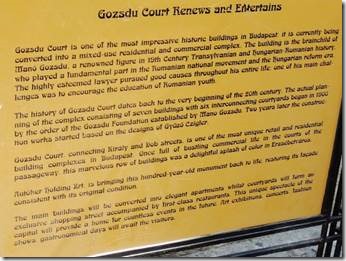

Gozsdu Court We visited the area on our walking tour and then returned Sunday for the market. “one family torn apart by war is too many” are the words written on the enlarged photo. Gozsdu Bazaar (GOUBA) is a weekly Sunday market held at the beautifully restored Gozsdu Courtyard, once the core of Budapest’s Jewish quarter. More than 100 vendors sell one-of-a-kind jewelry, clothes, accessories, antiques, home décor and more. It’s a great place to find unique gifts and souvenirs while being entertained by street performers and musicians. Gozsdu Courtyard connects Király utca and Dob utca and GOUBA can be accessed from both entrances at Király utca 13 and Dob utca 16. Opening hours: GOUBA is held every Sunday from April to mid October. It’s open 10 am to 7 pm. Entrance is free. http://visitbudapest.travel/local-secrets/gouba-gozsdu-bazaar/ The beautifully restored Gozsdu Courtyard, once the core of Budapest’s Jewish quarter, is popular with locals. Packed with restaurants, pubs and bars, the place comes alive every evening. Gozsdu Courtyard (Gozsdu Udvar) was a row of buildings with a series of inner courtyards connecting Király utca and Dob utca, with apartments on the top floors, and small shops and workshops on the ground floor. Recent renovations converted the old passageway into a modern residential and entertainment complex with some great restaurants and pubs. In addition, there’s GOzsdU BAzaar (GOUBA), a popular, open-air Sunday market held here from March to October. http://visitbudapest.travel/local-secrets/gozsdu-courtyard/ http://www.greatsynagogue.hu/gallery_gojdu.html tells more about Emanuil Gojdu and Győző Czigler, the architect who designed the complex. Neither man was Jewish but the area is located in what became and still is considered the Jewish quarter. |

|

“Located right next to the Gozsdu udvar and Carl Lutz Memorial, Spinoza Haz isa project reviving the cultural live of the Jewish quarter as it was before WWII. Spinoza Has is a complex of a fantastic restaurant –Café Spinoza, a theatre & toruist apartments. Every night there is live virtuous bar-piano music, every Friday Klezmer show, great food, great atmosphere all day long.” Baruch Spinoza “Finally, to turn to one of Spinoza’s most important and influential opinions, he denies that the Hebrew Bible is of divine origin. ….. If it is at all a “pious” and “divine” document, it is not because of its origin or the words on the page, but only because its narrative is especially morally edifying and effective in inspiring readers to acts of justice and charity—to practicing the “true religion.” http://www.neh.gov/ is a lengthy by interesting explanation of Spinoza’s philosphy and how his expulsion from the Portuguese Jewish community in Amsterdam can be explained by the history of that community. |

|

Ruin bars are all the rage in Budapest and have been around for 10 years since the founding of Szimpla Kert, the mecca of all ruin bars. These bars are built in Budapest’s old District VII neighborhood (the old Jewish quarter) in the ruins (hence the name) of abandoned buildings, stores, or lots. This neighborhood was left to decay after World War II so it was a perfect place to develop an underground bar scene. (Not so underground anymore though.) Each of these ruin bars has its own personality, but they all follow a few basic principles: find an old abandoned place, rent it out (maybe?), set up a bar, fill it with flea market furniture, have a few artists come in to leave their mark on the walls and ceiling, add in some weird antiques, serve alcohol, and watch people flock in. Since all these bars are in abandoned buildings, they open, close, and move frequently depending on whether the neighbors find out, the patrons get too loud, or an investor comes and buys the property to renovate it. This gives the whole concept an edge of excitement as you never know when these places will come and go. When you are in these bars, you feel like you are drinking at your local thrift store. None of the furniture matches. It’s all old. It’s eclectic. It feels like they just ransacked your grandmother’s house. The ceilings are all designed differently. For example, Instant has a room where the furniture is on the ceiling and Fogashaz has bikes hanging from its ceiling. The places haven’t been repaired or fixed up. There are still holes in the walls and pipes can be seen everywhere. http://www.nomadicmatt.com/ |

|

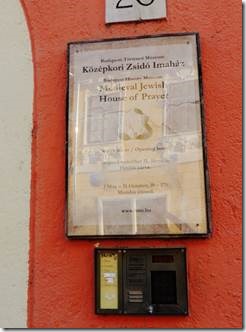

“Medieval Jewish Prayer House (Középkori Zsidó Imaház) built in 1364 on Castle Hill. A small medieval Sephardic synagogue functioning until 1686, right next to the former Great Synagogue in Buda.” |

The Seventh District: A Cultural Journey through Budapest’s Jewish Quarter

Budapest’s seventh district, Erzsébetváros, is one of the most culturally and historically rich parts of the city, and is home to the ancient Jewish quarter. Rosie Higham-Stainton explores this district, which offers a fascinating insight into the history of Hungary and its Jewish community.

Standing outside the Rumbach synagogue in Budapest’s Seventh District, still partly boarded up following the atrocities of World War II, I can hear the jazz sounds of a double bass drifting from the entrance. Inside the dimly lit space, the rows of seats are empty and the band on stage in the distance is in full ‘practice’ swing. It is not Klezmer music and there are no Yiddish or Hebrew lyrics; it is perhaps instead a sound born from the coming together of cultures that is a noticeable feature of Pest’s Seventh District and the surrounding area.

Still referred to today as the ‘ghetto’, the heritage of the Seventh District rests heavily with the Jewish community. However, it is also emerging as an area with a thriving creative scene and a new influx of shabby, arty drinking holes known as ‘ruin bars’. There are restaurants catering for tourists and locals alike, as well as a host of glitzy home interiors shops. This is the Seventh District today — drawing from both its cultural heritage and its thriving contemporary culture in an eclectic mix that could attract comparisons with London’s once Jewish, and now creative and highly diverse, East End.

Not far away is the most conspicuous and famed Jewish tourist attraction in Pest: the Dohány Utca Synagogue. This commanding structure, once the largest synagogue in Europe, was renovated and cleaned up after the Second World War with financial support from Jewish organisations and Hollywood actor/director Tony Curtis, whose own ancestry is one of Hungarian Jewry. It is a vast site containing not only the synagogue itself but also a Jewish museum and memorial garden to commemorate those lost during World War II. Queues of tourists line the streets for guided tours whilst policeman guard the perimeter fence day and night.

In reality, few Jews still live in the Seventh District, however slipping away from the shiny Dohány synagogue you will still find the smaller synagogues and food shops that are a vital element of the community’s day-to-day life. The real Jewish amenities of this area are not always obvious — kosher restaurants sit behind tinted windows on dusty side streets and unfussy cake shops go on producing their prize treats without too much ceremony – but they are there, huddled in between the different elements of what is a constantly evolving part of Pest.

In Michael Jacobs’ invaluable Budapest – A Cultural Guide the author writes, ‘the assimilation of Hungarian culture by non-Hungarians was a remarkable feature of Budapest’s late nineteenth century development, and particularly evident in the case of Hungary’s ever-increasing Jewish community’. He goes on to say ‘the Jewish community came to include not only a high proportion of Budapest’s most prominent bankers and industrialists (notably the creators of the city’s all-important textile and milling industries) but also, by 1910, two-fifths of the city’s lawyers, three-fifths of its doctors, and two fifths of its journalists; by then, Jews accounted for a quarter of the city’s population and had earned the place the nickname ‘Judapest’. This large Jewish element undoubtedly added a necessary cosmopolitan element to a city which had become increasingly xenophobic’. As Jacobs notes, the Jewish quarter was a thriving space of commerce, religion and culture, and it remains so to this day in varying forms.

Any Jewish ‘pilgrimage’ to the Seventh District and beyond is an interesting culinary and architectural adventure. From Moorish elements, such as the ochre colours and bulbous towers of the commonly known Rumbach synagogue, designed by the celebrated Viennese architect Otto Wagner to the very private Venetian styled Orthodox synagogue, places of worship represent Jewish tradition together with an age-old assimilation and embrace of other cultures.

The modest and unflashy Jewish food suppliers and restaurants are worth investigating for the wonderful delicacies specific to Ashkenazi Jews. The Jewish cake shop Frohlich Cukraszda on Dob Utca is one of the oldest and is famed for its offerings, in particular cakes and pastries containing the traditional filling of sweet ground poppy-seed paste. In more recent years a competitor has appeared nearby on Wesselenyi Utca. Noe Cukraszda, run by an entrepreneurial Jewish-Hungarian woman and her husband, it offers wonderful tiered cakes or flodni (Hungarian Jewish cake) with gooey nuts and poppy-seeds. Rachel, the owner, has established herself as a cake-maker extraordinaire, appearing on cookery shows and running mobile cake stalls at both local markets and the grand central market, simultaneously demonstrating her very 21st century approach and people’s flourishing interest in Jewish cuisine and culture.

For the brave (and appropriately attired!), there is Hanna’s restaurant within the walls of the orthodox synagogue, where goose soup and other traditional cuisine is available to tourists at a slightly elevated price. However, hidden away down side streets you will find the real thing – from the traditional, white linen table cloth atmosphere of the Kispipa Etterem to the plastic chairs and counter service of Zamatka Kifozde; pickled cabbage and cucumber, chicken noodle broths and cholent are all worth trying.

In what could be seen as a sign of the times, a Yiddish-Italian restaurant is soon to open in the beautiful Gozsdu Udvar, or Seven Courtyards. The notion of kosher pizza and other crossover dishes, perhaps targeted at tourists, may leave you with a sense of bemusement; however, it not only implies a thriving Jewish culture, but also an adapting and imaginative one. The curiosities of Jewish Pest are not clean cut or stalwart; they are steeped in both tradition and the ongoing cultural change of this fascinating city.

By Rosie Higham-Stainton

The Culture Trip

The Culture Trip showcases the best of art, culture and travel for every country in the world. Have a look at our Hungary or Europe sections to find out more or become involved.

http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/ discussion of organs in synagogues. Organs in synagogues is not agreed upon by all branches of the religion.

Andrew Salamon

In 1939, Budapest, Hungary was a beautiful and lively metropolis, gracing

the banks of the Danube River. Six years later, the city lay in shambles, and 460 000 Jews had been killed. This is the remarkable story of one Jewish boy who survived those years…

http://remember.org/jean/index.htm

The world-famed festival of European magnitude has made its first and most important goal to introduce Jewish culture to the widest circle of audience possible, and to highlight the importance of peaceful cultural coexistence with the diversity of programs.

It must be noted that an event-series belonging to a minority must emphasize tolerance just as much as it emphasizes taking on a cultural role.

The force that culture represents in bringing people together is of vast importance, as the media mostly mentions war and problems regarding Jews andIsrael. Yet, such a festival shows a different facade of the people, common to all mankind.

Every nation has it magnificent artists, regardless of being Christian, Jewish or Muslim. Every religion safeguards its own book and God and fears all others who are different. A decade and a half ago this festival was brought to life to begin a dialogue and go against exclusion, to break out of the frames we put others in.

Our multi-art event-series introducing Jewish culture and many other traditions of other nations has outgrown itself and is by now the biggest Jewish cultural festival ofEurope.

The Jewish Summer Festival ofBudapestis generally known to be a non-religious, but a cultural event series.