Puteri Harbour Marina,

Johor Malaysia

Hi All,

This is my last email about our Tibet/Kathmandu adventure. It seems as if it has taken longer to write about it than to actually live it. And it has only been the last week that when I wake up in the middle of the night I don’t have to figure out where I am. I really miss both Tibet and Nepal, but am getting back in tune with Puteri. Threre are quite a few cruisers here we like and we have started biking everyday when it’s not raining. When I shopt at my favorite vegetable stand at the Tuesday Night market, the owner calls me “sister” now. And thankfully, the man at the fried chicken stand now knows we want the breast so last night I didn’t have to illustrate. Randal usually points to his chest when he’s there, but he skipped the trip last night. We’ll soon move the boat to Sebana Cove where it will stay while we go home to the US. The man who had recovered our boat cushions is there and Randal has another project for him. We like to bike around that area too. And there are monkeys, amonitor lizards, and an occassional wild pig for entertainment. The development frenzy around Puteri has leveled most of the forest so there’s not much to see or do right here at the marina. One day there will be with all of the plans for this area, but we’ll be long gone into the Med and who knows where.

Ru

Kathmandu – part 3…….The End

We ate breakfast here every day, lunch and dinner many days.

They had wifi, good salads, wraps and large portions of food and were located next door to our hotel. We chatted often with one young waiter who always seemed to be there when we were no matter what time of day. One day he came to our table and invited us to go to his home and attend the wedding of his friend. Randal said sure (which surprised me) and asked where he lived. He said that we would have to fly there but that we would stay with him for a few days! We made sure that we understood his Nepalese English and indeed he did live a good distance from Kathmandu. We thanked him but said that we were leaving in a day so really didn’t have the time. He was quite disappointed. He was a very sweet young man and very capable. Randal gave him some money and asked if he would use it to buy a wedding gift for his friend. I wish I had a photo to show you. We wish him well.

“Our seats” where we ate, used the wifi and just sat and read.

This sign was over the cash register where you paid. Great idea!

You know you’re not in Kansas when the bank’s named Siddhartha.

No one knows MLB but they do know FIFA.

Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA)

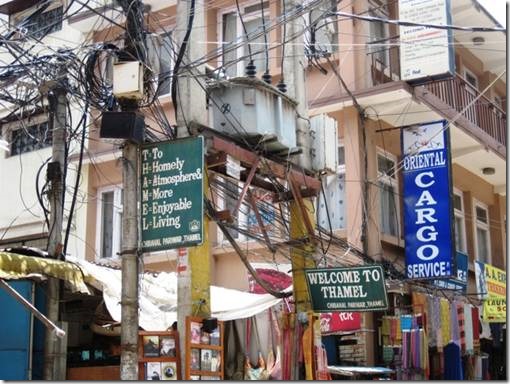

Thamel was a colorful jumble of everything packed into a small area referred to as the “tourist ghetto.”

Narrow streets full of shop keepers inviting you in “just to look.”

It was a great place to buy heavy wool sweaters and professional level trekking gear neither of which we need. But it was fun to look.

Lots of great used book shops though the prices weren’t as good as Singapore’s Brash Basha.

Who are the Gurkhas?

“Gurkhas have been part of the British Army for almost 200 years, but who are these fearsome Nepalese fighters?

“Better to die than be a coward” is the motto of the world-famous Nepalese Gurkha soldiers who are an integral part of the British Army.

They still carry into battle their traditional weapon – an 18-inch long curved knife known as the kukri.

In times past, it was said that once a kukri was drawn in battle, it had to “taste blood” – if not, its owner had to cut himself before returning it to its sheath.

Now, the Gurkhas say, it is used mainly for cooking.

The potential of these warriors was first realised by the British at the height of their empire-building in the last century.

The Victorians identified them as a “martial race”, perceiving in them particularly masculine qualities of toughness.

After suffering heavy casualties in the invasion of Nepal, the British East India Company signed a hasty peace deal in 1815, which also allowed it to recruit from the ranks of the former enemy.

Following the partition of India in 1947, an agreement between Nepal, India and Britain meant four Gurkha regiments from the Indian army were transferred to the British Army, eventually becoming the Gurkha Brigade.

Since then, the Gurkhas have loyally fought for the British all over the world, receiving 13 Victoria Crosses between them.

More than 200,000 fought in the two world wars and in the past 50 years, they have served in Hong Kong, Malaysia, Borneo, Cyprus, the Falklands, Kosovo and now in Iraq and Afghanistan.

They serve in a variety of roles, mainly in the infantry but with significant numbers of engineers, logisticians and signals specialists.

The name “Gurkha” comes from the hill town of Gorkha from which the Nepalese kingdom had expanded.

The ranks have always been dominated by four ethnic groups, the Gurungs and Magars from central Nepal, the Rais and Limbus from the east, who live in hill villages of impoverished hill farmers.

They keep to their Nepalese customs and beliefs, and the brigade follows religious festivals such as Dashain, in which – in Nepal, not the UK – goats and buffaloes are sacrificed.

But their numbers have been sharply reduced from a World War II peak of 112,000 men, and now stand at about 3,500.

During the two World Wars 43,000 young men lost their lives.

The Gurkhas are now based at Shorncliffe near Folkestone, Kent – but they do not become British citizens.

The soldiers are still selected from young men living in the hills of Nepal – with about 28,000 youths tackling the selection procedure for just over 200 places each year.

“ If there was a minute’s silence for every Gurkha casualty from World War II alone, we would have to keep quiet for two weeks ”

Gurkha Welfare Trust

The selection process has been described as one of the toughest in the world and is fiercely contested.

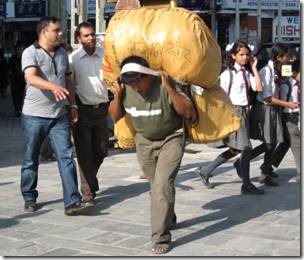

Young hopefuls have to run uphill for 40 minutes carrying a wicker basket on their back filled with rocks weighing 70lbs.

Prince Harry lived with a Gurkha battalion during his 10 weeks in Afghanistan.

There is said to be a cultural affinity between Gurkhas and the Afghan people which is beneficial to the British Army effort there.

Historian Tony Gould said Gurkhas have brought an excellent combination of qualities from a military point of view.

He said: “They are tough, they are brave, they are durable, they are amenable to discipline.

“They have another quality which you could say some British regiments had in the past, but it’s doubtful that they have now, that is a strong family tradition.

“So that within each battalion there were usually very, very close family links, so when they were fighting, they were not so much fighting for their officers or the cause but for their friends and family.”

After the Gurkhas have served their time in the Army – a maximum of 30 years, and a minimum of 15 to secure a pension – they are discharged back in Nepal.

Historically, they received a much smaller pension – at least six times less – than British soldiers, on the grounds that the cost of living is much lower in Nepal.

But with more choosing to settle permanently in the UK with their families, campaigners said this left them suffering considerable economic hardship.

They won a partial victory in March 2007, when Defence Minister Derek Twigg announced that all those who retired after July 1997 would get the same pension as the rest of the Army.”

Story from BBC NEWS:

http://news.bbc.co.uk/go/pr/fr/-/2/hi/uk_news/2786991.stm

Published: 2008/03/18 16:32:24 GMT

Ram Kumar Khatri; a pretty interesting fellow.

Early one morning Randal and I were strolling through Thamel and were approached by Mr. Khatri. You know how that goes; you think “what’s he selling?” But he wasn’t selling anything unless you count the copy of Quarterly Development Review that we bought for $5. Mr. Khatri is the founder, editor and publisher of this journal as part of his quest to “contribute towards the Development of Women and Children, Environment and Tourism in Nepal.” According to his bio in the journal, Mr. Khatri was born January 1, 1945 in Kathmandu. He spent most of his working life at the Agricultural Development Bank retiring as Division Chief in December of 2002. He is currently enrolled as a PhD student in the Department of Economics, Tribhuvan University.

Randal makes a contribution

The journal includes a section to help promote tourism. Mr. Khatri asks visitors what they like most and least about Nepal. The comments are aimed at officials who can make changes, not at other tourists. He asked us about our goals for life too. Randal and I both commented on how friendly people seemed but how poor the country was and wondered what would change that. My goal was to get up in the morning and know I was the only one controlling my day! After we’d been chatting for a while he told us about the school he was building and invited us, not only to visit but to stay there for a while. Our second invitation in the same day! Again we had to say no because we were leaving the next day.

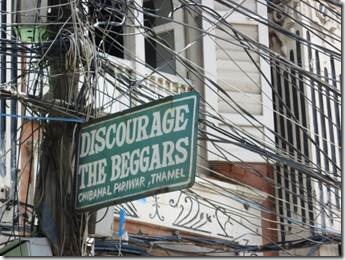

Another sign in the Thamel area.

During our day walking around Thamel we passed the same middle-aged begging woman about 5 times. The last time I passed her I was tired from walking around for fun. I thought of how she must have been feeling walking around all that time having to ask for money. She looked tired and discouraged and her skin looked a bit ravaged. I can’t remember what I gave her, more than a few bucks but not a great deal of money. Nepal is one of the poorest countries in the world. Hopefully Mr. Khatri can make a difference.

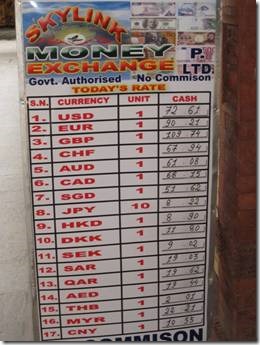

I was surprised that the $US was the first on the list and not the Euro.

This little boy was sitting outback behind his parents fruit stand eating up the profits!

And that’s about it. I think we short changed Nepal by only spending such a short time and that was my fault. Flights sort of dictated that we stay 4 days or 7 days and I thought 7 would be too many since we didn’t plan on doing any trekking. Friends who spent more time there seeing the countryside and trekking the mountain areas said they were beautiful. But so it goes….

The End….

Ru

DoraMac