|

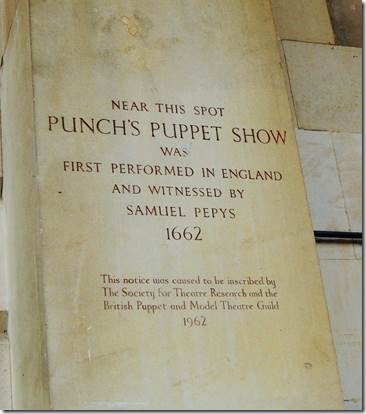

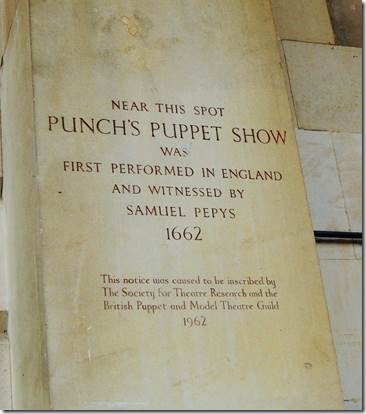

Punch and Judy at Covent Garden

“The earliest recorded evidence we have of Punch in England is from the 17th Century Diarist Samuel Pepys. Who, while on a visit to Covent Garden, on 9th May 1662, wrote…

“Thence to see an Italian puppet play that is within the rayles there, which is very pretty, the best that ever I saw, and great resort of gallants.”

Punch & Judy shows have stayed popular down the centuries because they have been kept topical. In wartime, Punch would fight and beat Hitler. In more recent times, Tony Blair, has even made an appearance!

http://www.thepjf.com/history_of_punch_and_judy.html

“Mr. Punch’s influence on British culture is unparalleled. In 2006, the Punch and Judy show was named one of 12 icons of Englishness by the British government’s Department for Culture, Media and Sport—right up there with a cup of tea and the double-decker bus. To celebrate his 350th birthday in 2012, Mr. Punch was treated to an entire year of parties and was the focus of a six-month-long exhibition about him at the venerable Victoria & Albert Museum of Childhood.

But this most English of entertainers isn’t actually English in origin—he’s Italian

Read more: http://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/Are-Punch-and-Judy-Shows-Finally-Outdated-189665711.html#ixzz2enQ7LwT2

Samuel Pepy (another one of those people a liberal arts education should have included.)

“Pepys’s diary is not so much a record of events as a re-creation of them. Not all the passages are as picturesque as the famous set pieces in which he describes Charles II’s coronation or the Great Fire of London, but there is no entry which does not, in some degree, display the same power of summoning back to life the events it relates.

Pepys’s skill lay in his close observation and total recall of detail. It is the small touches that achieve the effect. Another is the freshness and flexibility of the language. Pepys writes quickly in shorthand and for himself alone. The words, often piled on top of each other without much respect for formal grammar, exactly reflect the impressions of the moment. Yet the most important explanation is, perhaps, that throughout the diary Pepys writes mainly as an observer of people. It is this that makes him the most human and accessible of diarists, and that gives the diary its special quality as a historical record.

Instead of writing a considered narrative, such as would be presented by the historian or biographer or autobiographer, Pepys shows us hundreds of scenes from life – civil servants in committee, MP’s in debate, concerts of music, friends on a river outing. Events are jumbled together, sermons with amorous assignations, domestic tiffs with national crises.

The diary’s contents are shaped also by another factor – its geographical setting. It is a London diary, with only occasional glimpses of the countryside. Yet as a panorama of the seventeenth-century capital it is incomparable, more comprehensive than Boswell’s account of the London a century later because Pepys moved in a wider world. As luck would have it, Pepys wrote in the decade when London suffered two of its great disasters – the Plague of 1665 and the Great Fire of the following year. His descriptions of both – agonisingly vivid – achieve their effect by being something more than superlative reporting; they are written with compassion. As always with Pepys it is people, not literary effects, that matter.”

http://www.magd.cam.ac.uk/samuel-pepys/

|