Shalom

In about 30 minutes we’re walking across the dock to have dinner on the boat of our friend Eve. She is making falafel for us. It was on Eve’s boat that we had Chinese food and blintz wrapped egg-rolls for Passover. Tomorrow we’re all going to meet the English Speakers of Ashdod Club members at their weekly get-together at Cafe Hillel at the City Mall a 15 minute walk from here. Most things are a 15 minute walk from here which is great.

One of my favorite places that we visited in Tel Aviv was the Museum of the Diaspora. It is on the campus of Tel Aviv University. We spent several hours; you could have spent several days. Here are my impressions.

Ru

ps I guess my request from the Torah scribe at Masada that the Sox win the World Series (and for world peace) wasn’t so goofy after all. The Sox are doing great! Now if the “world peace” part could be so easy…..

Israel Museum of the Diaspora Beit Hatfutsot

“Beit Hatfutsot, the Museum of the Jewish People, is more than a museum. This unique global institution tells the ongoing and extraordinary story of the Jewish people. Beit Hatfutsot connects Jewish people to their roots and strengthens their personal and collective Jewish identity. Beit Hatfutsot conveys to the world the fascinating narrative of the Jewish people and the essence of the Jewish culture, faith, purpose and deed while presenting the contribution of world Jewry to humanity.”

“Outsiders looking in on this singular people often tend to form stereotype, like the rapacious hook-nosed moneylender of anti-Semitic cartoons. Actually the Jew of the Diaspora might be almost anything: farmer, trader, shopkeeper, silversmith for the Yemenites, slave trader for the Kings of Bohemia, lion tamer for the Kings of Aragon, and his physical traits might vary as much as his choice of trades.

“This spectrum is richly illustrated in a display where lights are continually flashing in the darkness as 16 screens project photographic galleries of Jewish faces throughout the contemporary world. There are some 200 in all – blond Jews, black Jews, sturdy mountaineers and gentle scholars, a vast array of facial characteristics, a cross-section of mankind.”…….

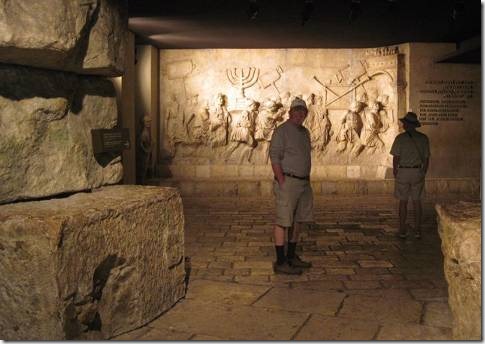

“Beth Hatefutsoth is intended to be a record of achievement, and its prevailing tone is one of victory over recurring difficulties. But there are continual reminders that the great victories are balanced by great disasters, that a recurring theme of Jewish history has been woe. The visitor walking up from floor to floor climbs a circular stairwell in which there hangs from the ceiling a cagelike iron structure 50 feet high designed by Charles Forberg of New York. An eerie light in the center and solemn music help identify this as a memorial column, commemorating centuries of martyrdom. At its foot are “Scrolls of Fires” – illuminated poems recalling the great tragedies that have befallen the Jews since 586 BC, when Solomon’s Temple was destroyed, down to Hitler’s holocaust of 1939-45. ………

“Outside the building the visitor steps back into the peaceful university canvas. Students are running on the grass between courses. The exiles are safely at home. But it takes no more than the distant whine of an Army fighter plane or the siren on an ambulance that may be on its way to the scene of a suicide bombing to recall that the final chapter is not yet written, the story has no guarantee of a happy ending.

©1978, 2003 Robert Wernick Smithsonian Magazine June 1978

One of the security entrances into Tel Aviv University. http://www.tau.ac.il/index-eng.html

“Outside the building the visitor steps back into the peaceful university canvas.”

Located in Israel’s cultural, financial and industrial heartland, Tel Aviv University is the largest university in Israel and the biggest Jewish university in the world. It is a major center of teaching and research, comprising nine faculties, 106 departments, and 90 research institutes. Its origins go back to 1956, when three small education units – The Tel Aviv School of Law and Economics, an Institute of Natural Sciences, and an Institute of Jewish Studies – joined together to form the University of Tel Aviv.

A Role In The Peace Process

Middle Eastern history, strategic studies, and the search for peace are central concerns for Tel Aviv University researchers. The Institute for Diplomacy and Regional Cooperation, founded by the Peres Center for Peace, the Armand Hammer Fund for Economic Cooperation in the Middle East, the Moshe Dayan Center for Middle Eastern and African History, the Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies, the Tami Steinmetz Center for Peace Research and the Morris E. Curiel Center for International Studies are respected sources of information for government and private institutions, the press and the public. University scholars are putting their expertise to work for the peace process, participating in Israel’s delegations to the peace talks, and in joint projects with colleagues from neighboring countries.

A bird waits patiently for what the cat will leave behind.

Art was everywhere.

From one angle this sculpture looked like a butterfly, from another someone running.

You go up some white steps into a huge building and because your friends Nilly and Eitan told you the museum was free on “International Museum Day” you get to skip the cashier line.

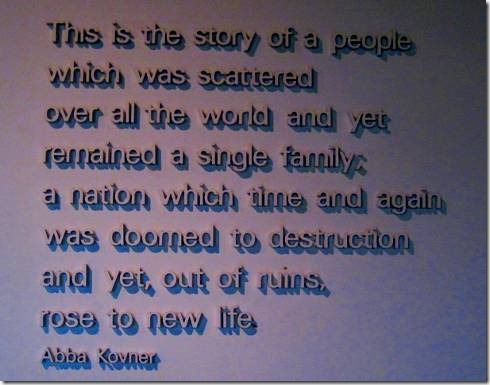

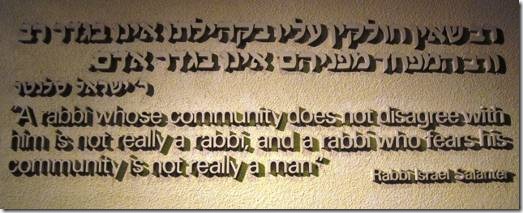

In this museum the words captured my imagination almost more than the images did.

We started walking through the museum during ancient times…..

Two of my favorite quotations…….

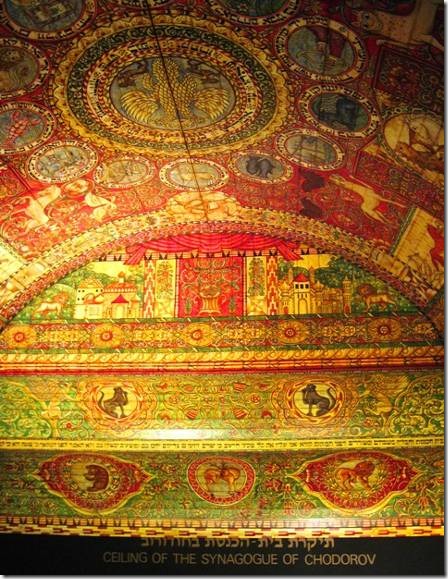

Chodorov Synagogue Ceiling

The lovely ceiling paintings of the 17th century wooden synagogue of Chodorov were consumed by German fire in World War II. Only black and white photographs survived, but artists could use these and surviving bits of contemporaneous work to bring back to life their scampering animals and green meadows. http://www.robertwernick.com/articles/diaspora.htm

The museum has a genealogical center so I stopped to look up my family name, Lipnik. My mother’s maiden name was Horowitz and I assumed there would be thousands of hits for that, but not for Lipnik.

You can see the computer cursor in my photo of the screen where I was researching.

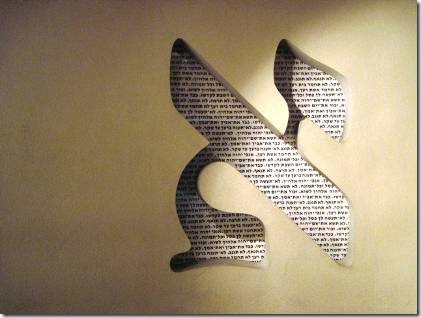

The Hebrew letter Aleph

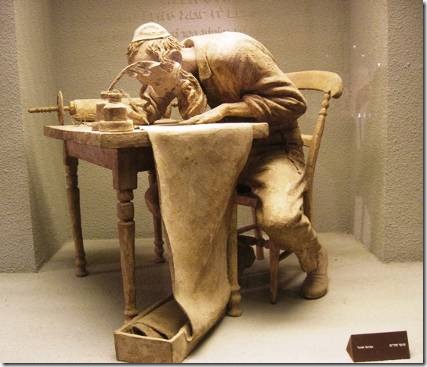

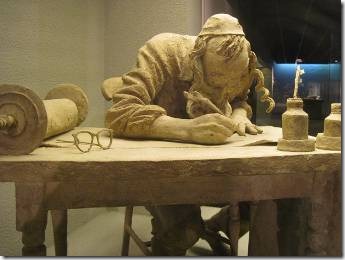

A wonderful exhibit showed the importance of the alphabet, writing, reading and learning to Jews.

This diorama spoke to me as I’d been practicing the Hebrew alphabet and not having an easy time. I don’t remember it being so hard as a kid.

Newspapers took great importance to the Jewish community as it linked them to the national and social movements around the world. I remember my mother talking about family members reading the Jewish newspapers. My Aunt Jennie was quite a socialist. And my mother voted for someone Dean Alfange who ran for Governor of New York on the Socialist Labor Ticket He lost, but I won as I had his son for my Constitutional Law professor at U Mass so managed to get a B in the class after getting a D in the midterm. Actually I did really well on the final but got the D (rather than something worse) because of my mom. It probably should have been an F. I understood the work in class, but there was something about that mid-term. But none of that matters any more except as an aside to this photo.

Now when lots of Jews leave a place they call it a “Brain Drain.”

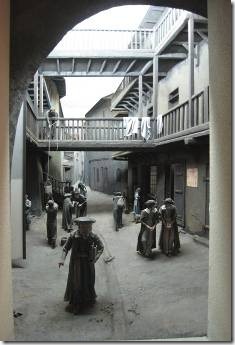

The Jews of Lublin Poland 1619.

Lublin once served as one the most important centers of Jewish life, commerce,

culture, and scholarship in Europe. It had the world’s largest Talmudic school. www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/vjw/Lublin.html

Images of the Jewish world seen through a candelabra cut from the wall.

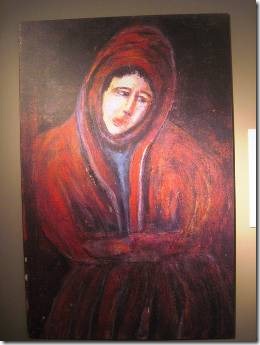

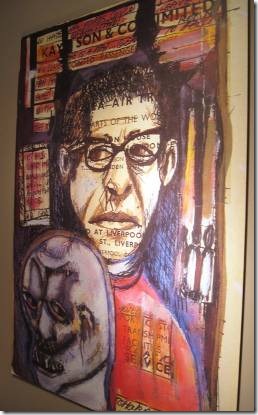

There was an exhibit devoted to the capture and trial of Adolf Eichmann. I followed the story told in the paintings by Peter Zvi Malkin. Two articles about him follow. One is his obituary from the New York Times. The other is a really fascinating article from the Smithsonian.

Chester Higgins Jr./The New York Times, 2003 http://www.nytimes.com/2005/03/03/obituaries/03malkin.html

Peter Zvi Malkin

Peter Zvi Malkin, a former Israeli intelligence agent who in 1960 captured Adolf Eichmann in Argentina, and who afterward captured him again and again on paper in his second career as a painter and writer, died on Tuesday in a rehabilitation facility in Manhattan. He was believed to be 77, and he had homes in Manhattan and Tel Aviv.

Mr. Malkin, who was recovering from a blood infection he contracted several months ago, choked to death after vomiting, Gabriel Erem, a longtime friend, said.

A Mossad agent for 27 years, Mr. Malkin was the author of a memoir, “Eichmann in My Hands” (Warner, 1990). Written with Harry Stein, it chronicles Mossad’s pursuit and capture of Eichmann, an architect of the Final Solution, the systematic Nazi program to exterminate Jews.

A master of disguises, Mr. Malkin often posed as an itinerant painter during intelligence-gathering missions. Repelled and fascinated by Eichmann during the time he spent guarding him in Argentina, he began surreptitiously sketching his portrait. Eichmann was later spirited out of the country by Mossad to stand trial in Israel; he was convicted of crimes against humanity and other charges and executed in 1962.

In an interview last night, Robert M. Morgenthau, the Manhattan district attorney, called Mr. Malkin “an absolutely extraordinary man, probably the last century’s greatest intelligence agent.” Starting in the late 1970’s, Mr. Malkin assisted Mr. Morgenthau on several cases, including the investigation of Frank Terpil, a C.I.A. operative convicted of selling weapons and explosives to Libya and Uganda. Mr. Terpil fled the United States and remains a fugitive.

A two-volume collection of Mr. Malkin’s art, “The Argentina Journal” and “Casting Pebbles on the Water With a Cluster of Colors,” was published by VWF Publishing in 2002. Mr. Malkin, who retired from Mossad in 1976, was also a private consultant on counterterrorism in later years.

Zvi Malchin was born, most likely on May 27, 1927, either in Poland (according to his son, Omer) or in British Palestine (according to Mr. Malkin’s Web site).

“With him, it depends on what passport you’re looking at,” Omer Malkin said by telephone yesterday. Mr. Malkin adopted the name Peter and anglicized the spelling of his last name as an adult, his son said.

Mr. Malkin’s son and Mr. Malkin’s Web site agree that Mr. Malkin spent his early childhood in Poland. In 1936, with rising anti-Semitism there, his family settled in Palestine. Mr. Malkin’s sister, Fruma, and her three children remained behind in Poland. All died in the Holocaust, along with many of Mr. Malkin’s other relatives.

As an adolescent, Mr. Malkin joined the Palestine Jewish underground. After the creation of the State of Israel in 1948, he was recruited by Mossad; he eventually became the organization’s chief of operations.

In the spring of 1960, Mr. Malkin was part of a team of agents sent to Buenos Aires to kidnap Eichmann, who was living in a suburb under the alias Ricardo Klement. A creature of meticulous habit, Eichmann was rigorously punctual, returning home by the same bus each evening from his job at a Mercedes-Benz factory.

On May 11, Eichmann alighted from the bus and walked toward his house on Garibaldi Street. Mr. Malkin approached him and uttered the only words of Spanish he knew, “Un momentito, Señor.” He grabbed Eichmann’s arm. As he told The New York Times in 2003, he wore gloves so he would not have to touch the man.

Concerned about bystanders, Mr. Malkin was unarmed. In an interview in 2003 with Midstream magazine, a monthly Jewish review, he explained, “Obviously, we couldn’t tell people, ‘We are going to capture Eichmann, so please stay away.’ ”

Mr. Malkin and his colleagues wrestled Eichmann into a waiting car and drove him to a “safe house,” where he was interrogated for 10 days. Standing guard over Eichmann during this time, Mr. Malkin began quietly to draw him, using the sketch pencils, acrylic paints and makeup he carried in his disguise kit.

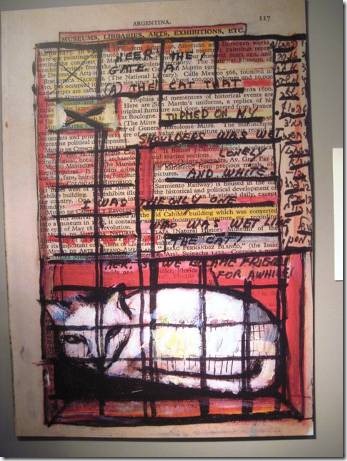

He drew on the only surface that came to hand, a South American travel guide he had purchased for the trip. The results, portraits of Eichmann and other images of the Holocaust superimposed on yellowing pages of maps and text, are hauntingly beautiful. The images, along with Mr. Malkin’s later work, may be seen on Mr. Malkin’s Web site, www.peterzmalkin.com.

Besides his son, of Los Altos, Calif., Mr. Malkin is survived by his wife, the former Roni Thorner; two daughters, Tami and Adi, both of Israel; and eight grandchildren.

Because of the extreme secrecy Mossad demanded, Mr. Malkin for many years said nothing about his role in Eichmann’s capture. As he recounted to Midstream magazine, he broke his silence only when his mother was on her deathbed. “Mama,” he told her, “I captured Eichmann. Fruma is avenged.”

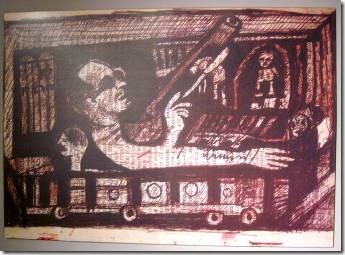

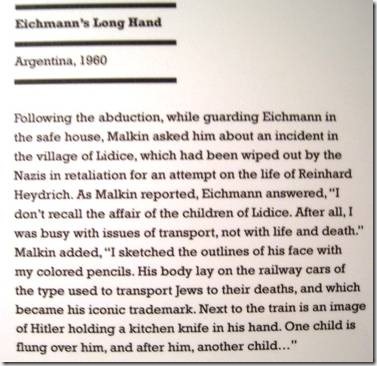

Eichmann’s Long Hand

——————————————————————————–

December 25, 2005

Peter Zvi Malkin | b. 1927

Chasing Evil

By DANIEL BERGNER

Peter Malkin wore a pair of fur-lined leather gloves when he seized Adolf Eichmann on a street in suburban Buenos Aires. It was 1960.

For 15 years, one of the chief engineers of Hitler’s Final Solution had escaped capture. Now Malkin, the point man of a small team of clandestine Israeli agents, helped to wrestle him into the back of a waiting car and, Malkin would recount in his memoir, “Eichmann in My Hands,” written with Harry Stein, pressed his hand over Eichmann’s mouth so he could not scream. Malkin wore the gloves, he wrote, because “the thought of placing my bare hand over the mouth that had ordered the death of millions, of feeling the hot breath and saliva on my skin, filled me with an overwhelming sense of revulsion.” But the leather and fur weren’t enough. They were quickly “soaked through with his spittle.”

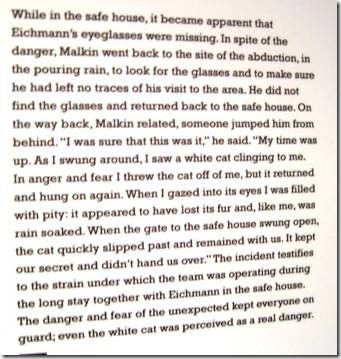

It was the beginning of strange intimacy. Malkin – whose sister had been killed along with her children in Poland during the Holocaust, after Malkin, his two brothers and his parents managed to flee to Palestine – had already prepared a bedroom for Eichmann in the safe house where the agents would keep him hidden until, against international law, they could spirit him out of Argentina to stand trial in Israel. Malkin had made the bed with fresh sheets and laid out a towel and toiletries and a pair of striped pajamas. The room, where Malkin would spend much of the next 10 days in solo shifts watching over one of the 20th century’s greatest murderers, was spare and tiny; captor and captive, alone, were never more than two or three steps apart. A blanket covered the only window.

Malkin would wash and shave Eichmann’s face, tracing, over and over, the contours of his cheeks and jaw. Malkin fed him, lifting a spoon to his lips, and dressed and undressed him. (The memoir implies that Eichmann’s hands were kept loosely bound, yet the leader of the Israeli team, Rafi Eitan, told me recently that, after the first day, Eichmann’s hands were not bound during the daytime.) Malkin held Eichmann’s hands, aiding him as he did deep knee bends for exercise.

And when Eichmann said that he adored fine red wine, Malkin stole an expensive bottle that another agent had been saving for the Sabbath. He served him wine and played him music – a flamenco, a tango – on an old wind-up record player.

Partly, Malkin wrote, his ministering to Eichmann was an attempt to preserve him for public justice. In captivity, Eichmann became passive and seemed utterly incapable of caring for himself (Malkin had to bark orders at him to get him to move his bowels), and Malkin worried that his body and mind would deteriorate irreparably before he could be put on trial. Partly, too, Malkin’s caring was calculated seduction: he hoped that Eichmann would reveal the whereabouts of the fugitive Nazi doctor Josef Mengele, and that Eichmann would sign a document stating that he was traveling to Israel to stand trial of his own free will. But meanwhile, in a way, the killer became Malkin’s muse.

Malkin – an explosives specialist in the fight for Israeli statehood before he was recruited into the Israeli intelligence services – was an expert in disguises and an amateur painter, avid and skilled. Within the room’s close walls, with oil-based pencils from his disguise kit, he began to evoke Eichmann on the pages of a guidebook to South America, which he’d brought along on the mission. The first portrait (above) was done in black and gray on a map of Argentina. Eichmann might simply be a tired clerk, an accountant worn down by numbers, with just a tentative suggestion of emotional depth, of self-reflection, of conscience, in the blurred black irises of the eyes.

“Then I flipped the page and did him in his SS regalia,” Malkin wrote. “I continued drawing in a kind of frenzy. Now I had him watching a railroad train, counting the cars; now in abstract, lying prone atop a flatcar, bearing a machine gun; now, on facing pages, appeared Hitler and Mussolini; now my parents and, in muted pastels, her eyes immense and brooding, my sister, Fruma.”

As days and nights went by, Malkin told none of the other agents about his portraits of their prisoner; Eichmann was the only one who knew, remarking, when Malkin turned the guidebook and showed him a work in progress, an image of himself, “Nice. Very nice.” Nor, at first, did Malkin tell anyone about their conversations: dialogues spurred by Malkin’s questions about the killer’s motives; talks driven by the prisoner’s fear for his family; chats about music or the pair’s “shared love of nature and the wild.” Malkin wasn’t supposed to converse with Eichmann at all; talk was to be left to sessions with the team’s official, harsh-tongued interrogator. And except as Eichmann ate or went to the bathroom, he was supposed to be kept blindfolded. Malkin broke this rule as well. “We found ourselves co-conspirators of a sort,” he wrote. “He knew as well as I did to fall silent at the sound of approaching footsteps.”

The touching of the face; the portraiture; the talks of Eichmann’s beloved young son and of all the children, like Fruma’s, he had sent to death (discussions during which Malkin barely controlled his voice and his rage, as he strained to coax words from Eichmann that would somehow offer explanation of his deeds); the removal of the blindfold – Malkin wanted desperately to see into him. By the end of the 10 days, the memoir relates, another of the agents, the team’s only woman, would accuse Malkin: “You act like you’re in love with him.” But the object of desire was elusive. In words, Eichmann gave up little beyond versions of what he would ultimately claim in court in Jerusalem, that in orchestrating the killing of millions he had merely followed orders. And in art, Malkin could create of Eichmann only unyielding surfaces.

During the years to come, Malkin would rise to be chief of operations in the Mossad, Israel’s famed intelligence agency. Later, in retirement, he devoted himself to his art. He collected and painted on maps from all over the world. Israel Perry, the owner of the Manhattan gallery that represents Malkin’s work, told me that Malkin used the maps for inspiration, to pull himself back into the past, back toward people and scenes that had floated by in his widely traveled, covert life. In this way, he found other subjects, other faces besides Eichmann’s; in this way, perhaps, he found other, easier paths to the human soul.

Copyright 2005The New York Times Company Home Privacy Policy Search Corrections XML Help Contact Us Work for Us Site Map Back to Top