Cheers,

Sunday Randal and I met up with friends Valerie and Steve for a day in Greenwich. Here’s the story.

Ru

Our friends Valerie and Steve live in Fleet, not so far from Gosport/Portsmouth; our first port of call in England. They came to visit us there for an afternoon. And just a few weeks ago, Valerie came to spend some time with us in London. At that time Steve was back in Thailand with their sailboat which they are in the process of selling. Steve returned to England for Christmas but with our plans and theirs we couldn’t work out a trip to Fleet so we decided to meet up for the day at Greenwich. None of us had ever been before so it seemed a good plan.

To fully explore Greenwich, you would need several days. We only had several hours so tried to see what was high on everyone’s list. We also limited ourselves to venues that were free since we didn’t have the time to fully make use of a 22 Pound ticket. ($35 per person.)

For anyone really interested in Greenwich and the story of the Prime Meridian I do recommend

Dava Sobel’s book Longitude which is the story of why the Prime Meridian is in Greenwich.

“Dava Sobel is a former science writer for the New York Times, as well as contributor to Audubon, Discover, Life, and Omni magazines. The concluding chapter of Longitude is a very touching account of her personal visit to zero longitude in Greenwich (where this writer also straddled that magic line embedded in the pavement). The Maritime Museum in Greenwich is the actual home of Harrison’s four clocks. Sobel writes, "Coming face to face with these machines at last, after having read countless accounts of their construction and trial, after having seen every detail of their insides and outsides in still and moving pictures, reduced me to tears."

http://www.thesocialcontract.com/artman2/publish/tsc0902/article_1014.shtml

|

0 degrees Longitude line free version. Valerie and I are in the East and Randal and Steve are in the West. But that’s okay with me as growing up in New Bedford, MA on the East coast, I always think anything is west of where I am. Living on the west coast of Turkey was something I really had to get used to. Good thing here in London we live in the East End. Somewhere in the Royal Observatory you can stand over the line, but that involved buying tickets so we opted for this free version. It was a really chilly day! While we were inside the Maritime Museum the sun shone, but as soon as we began the outside bits, the sky became gray and cloudy and by the end of the afternoon we had drizzle. |

Greenwich England is where East meets West at the Greenwich Meridian (0° Longitude); World Time is set Greenwich Mean Time. Remember the new millennium started in 2001.

There is the famous Cutty Sark to visit and the Royal Naval College. Just down river is the Thames Barrier (We saw the Cutty Sark)

The Royal Observatory at Greenwich is in Greenwich Park along with the National Maritime Museum and the Queens House (on which the White House in Washington DC, USA is based). (We visited the Queen’s House.)

The London Marathon starts in Greenwich Park every Spring.

Greenwich has a long heritage; it was the birth place of King Henry VIII and his daughters Queen Mary (Bloody Mary) and Queen Elizabeth I (The Virgin Queen).

It has seen many famous visitors from Peter the Great through Charles Dickens to Bob Hope.

http://wwp.greenwichengland.com/tourism/nmm.htm

Randal and I took the light rail from Tower Hill Station, changing trains once before arriving at the Cutty Sark stop just outside the historic park area. We’d planned to meet Valerie and Steve at the Maritime Museum entrance, but upon our arrival, learned there were two entrances. I called Valerie and Steve who were just arriving at the car park and told them we’d be in the coffee shop. Then I had to call them and tell them which coffee shop as there were two of those also.

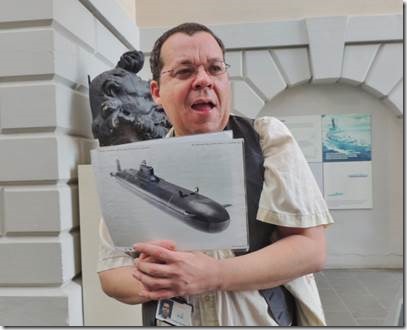

After our coffee we joined the free introductory tour of the Maritime Museum “highlights”. It turned into a private tour as there were only the 4 of us led by our guide Stephan, who, during the discussion of nuclear subs and the Cold War told us he had been one of the last members of the East German military.

|

National Maritime Museum back entrance where Randal and I entered. |

|

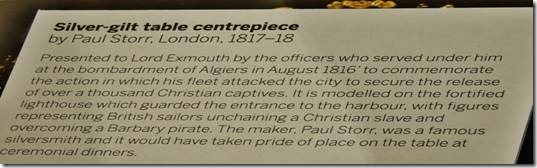

Our tour began with this massive creation…. |

|

Randal and I passed along the coast of Algeria on our way from Tunisia to Spain but didn’t stop in. |

|

Cold War history come to life… Our guide Stephen explaining to us how nuclear subs and battleships try to avoid generating any sounds that can be picked up by sonar detectors. That includes very very quiet propellers. |

|

The propeller that failed…though we stood below it we didn’t hear a sound, but it was deemed too noisy for action so was given to the museum. “The screw is motorized and rotates slowly. Information from sign: This bronze-alloy propeller was made for a Type-23 frigate, the core warship of the Royal Navy’s surface fleet. The propeller is specially designed to minimize underwater noise and prevent detection by enemy submarines. Combined with an innovative propulsion system, two low-speed propellers like this give the Type-23 frigate its reputation as an ultra-quiet anti-submarine ship. There are currently thirteen Type-23s in active service in the Royal Navy, making up half of the frigate/destroyer force. Powerful and versatile, these 133-metre (436 ft) ships are designed to take part in a wide range of tasks including surveillance, anti-piracy operations, disaster relief work. They are often called ‘Duke-class’ frigates as they are all named after British dukes. Type-23s were built at the shipyards of Swan Hunter (Tyneside) and Yarrow’s (Glasgow).” |

|

Miss Britain III looks like something from a James Bond movie http://www.cogg.co.uk/blog/napier-lion-king-of-engines-part-2.html tells the real story of the race for the Harmsworth Trophy in the 1930s. |

|

State Barge “This state barge was built for Frederick, Prince of Wales, eldest son of King George II. At around 19.2 m (63 ft) in length, it is one of the Museum’s largest objects. She was designed by the architect, landscape gardener and painter William Kent, and built by John Hall on the south bank of the Thames just opposite Whitehall in 1732. Kent’s drawings for the barge, including a hull plan, have been preserved at the Royal Institute of British Architects……….. The barge was often used for journeys of pleasure connected with paintings and music. In 1749, for a regatta in Woolwich she was decorated in the newly-Chinese style or chinoiserie, and the 21 oarsmen were dressed in oriental costume. (Stephen told us everything Chinese was in vogue at that time.) After Prince Frederick’s untimely death in 1751, the barge became the principal royal barge used by successive monarchs, together with Queen Mary’s shallop (also on display in the museum). In 1849 she made her last appearance afloat when Prince Albert with two of his children was rowed to the opening of the Coal Exchange. She was then sawn into three sections and stored in the Royal Barge House at Windsor Great Park for over 100 years before being brought to the Museum.” |

|

HMS Implacable “The Dugay Trouin, 74 guns, was launched at Rochefort in France in 1800. She was involved in the Battle of Trafalgar but managed to evade the victorious British fleet. The Dugay Trouin’s escape was short-lived and on 3 November 1805 a British squadron engaged her in the Bay of Biscay. In the ensuing battle, the captain of the Dugay Trouin was killed, her masts were shot away, and she was eventually captured after a gallant French defence. The ship was taken into the Royal Navy, renamed Implacable, and saw action in the Baltic in 1808-09 and off the Syrian coast in 1840. She became a training vessel for boy seamen at Devonport in 1855 and was finally placed on the navy’s disposal list in 1908. The ship was handed over to Geoffrey Wheatley Cobb for preservation in 1912 and sufficient money was raised to carry out a series of repairs at Plymouth in the 1920s. In 1932, HMS Implacable was towed to Portsmouth where she again served as a training establishment. The Admiralty requisitioned the vessel during the Second World War but it found the cost of her upkeep too great to bear and in 1947 it was decided to dispose of the Implacable. (She had been at the Battle of Trafalgar, albeit as an enemy ship; but Trafalgar is a really big deal here. RJ) This move caused a furious public outcry but, despite an appeal to save her, she was scuttled in 1949. The figurehead and stern carvings were preserved and presented to the Museum in 1950. The figurehead dates from her refit in Britain in 1805 and is a representation of the gorgon Medusa. Because of their scale, it was found impossible to display the stern carvings (which amount to some 160 objects) at the Museum and they were placed in store. However, with the opening of the redeveloped Neptune Court in 1999, both the stern and the figurehead of HMS Implacable have been brought together and can now be seen for the first time in 50 years. For more on the story of the Implacable and her remarkable career, see Implacable: A Trafalgar ship remembered (1999). |

|

Tarbat Ness Light “This light is the one designed by the N.L.B. Chief Engineer D.A. Stevenson in 1891. The glass lenses were made by Barbier & Co Paris, whilst James Dove, Edinburgh produced the mechanism. The loss of sixteen vessels in the Moray Firth storm of November 1826 brought many applications for lights on Tarbat Ness or Covesea Skerries. The former was given priority as it had been named in 1814 and was regarded as important by the Caledonian Canal Commissioners. The Tarbat Ness Lighthouse was engineered by Robert Stevenson and built by James Smith of Inverness. The light was first exhibited on 26 January 1830. The tower (41 m, with 203 steps) is the third tallest in Scotland (after North Ronaldsay and Skerryvore being taller) and bears two distinguishing broad red bands. The total elevation is 53 m and nominal range 24 miles, flashing (4) white every 30 secs. The light was an Argand Paraffin Lamp with 4 burners until 1907 when it was changed to an incandescent pressurised lamp with 55 mm mantles. The optic and lightroom machine now in the Museum were installed in 1892 and remained in use until automation in 1985.” http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/43189.html The Lighthouse Stevensons The extraordinary story of the building of the Scottish lighthouses by the ancestors of Robert Louis Stevenson (HarperCollins, 1999) Extract from the Introduction “Whenever I smell salt water, I know that I am not far from one of the works of my ancestors,” wrote Robert Louis Stevenson in 1880. “The Bell Rock stands monument for my grandfather, the Skerry Vhor for my Uncle Alan; and when the lights come out at sundown along the shores of Scotland, I am proud to think they burn more brightly for the genius of my father.” Louis was the most famous of the Stevensons, but he was not the most productive. Between 1790 and 1940, eight members of the Stevenson family planned, designed and constructed the 97 manned lighthouses which still speckle the Scottish coast, working in conditions and places which would be daunting even for modern engineers. The same driven energy which Louis put into writing, his ancestors put into lighting the darkness of the seas. The Lighthouse Stevensons, as they became known, were also responsible for a slew of inventions in both construction and optics and for an extraordinary series of developments in architecture, design and mechanics. As well as lighthouses, they built harbours, roads, railways, docks and canals all over Scotland and beyond; they, as much as anyone, are responsible for their country’s appearance today. But the family who became known as the Lighthouse Stevensons have gone down in history for a very different profession. Robert, the first of the Stevenson dynasty, despised literature; his grandson perpetuated his family’s name with it. The author of Kidnapped, Treasure Island and The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll & Mr Hyde was initially trained as an engineer. To his father’s dismay, Louis escaped aged 21, first into law and then into writing. As he later confessed in The Education of an Engineer, his training had not been used in quite the way his father intended. “What I gleaned, I am sure I do not know; but in deed I had already my own private determination to be an author; I loved the art of words and the appearances of life; and travellers, and headers, and rubble, and polished ashlar, and pierres perdues, and even the thrilling question of the string course, interested me only (if they interested me at all) as properties for some possible romance or as words to add to my vocabulary.” With age and distance, Louis recovered pride and affection in the Stevenson trade. He wrote with awe of his grandfather’s work on the Bell Rock lighthouse, and of his father’s melancholic genius for design and experimentation. He wrote about almost every aspect of his own brief and unhappy time as an apprentice, in essays, letters, introductions and memoirs. Most of all, Louis alchemised his experiences around the ragged coasts of the North into the gold of his best fiction; Treasure Island and Kidnapped both contain salvaged traces of his early career. The further he grew away from engineering, the more he felt towards it; he was sea-marked, and he knew it. He also recognised, with some discomfiture, that his own fame was swallowing up the recognition which his family deserved. In 1886, far from Edinburgh, he wrote crossly to his American publishers; "My father is not an ‘inspector’ of lighthouses; he, two of my uncles, my grandfather, and my great grandfather in succession, have been engineers to the Scotch Lighthouse service; all the sea lights in Scotland are signed with our name; and my father’s services to lighthouse optics have been distinguished indeed. I might write books till 1900 and not serve humanity so well; and it moves me to a certain impatience, to see the little, frothy bubble that attends the author his son, and compare it with the obscurity in which that better man finds his reward." Louis was only being a little disingenous; he liked recognition and, to an extent, courted it. But his plaintive belief that his family deserved the same acknowledgement seems far-sighted now. Even at the height of the Victorian engineering boom, great men went unnoticed and exceptional feats unrecognised. Louis did his best to remedy the injustice, but also recognised that the Stevensons hardly helped themselves. Not one member of the family ever took out a patent on any of their inventions in design, optics or architecture. All of them believed that their works were for the benefit of the nation as a whole and therefore unworthy of private gain. They were only engineers, after all; they worked to order or conscience, and were only rarely disposed to flightier moments of reflection. What pride they had in their creations they put down to the advantages of forward planning and the benevolence of the Almighty. And Louis, the tricky, charming black sheep of the family, stole all the fame that posterity had to give.” http://www.bellabathurst.com/writing02.php |