We ate lunch at one of the many restaurants in the Boudhanath plaza and then drove through more dusty traffic to the Pashupati Development Area. I instantly felt like I was in a scene from the BBC production The Jewel in the Crown. The complex was huge and unlike any other place I have ever visited. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pashupatinath_Temple gives you the basics but David and Ronnie on their website http://www.project-7.se/?m=201007 give a really humanistic description of the place and Kathmandu in general. You have to scroll down the page to find the entry about Nepal, but their combination Swedish/French/English is charming and humorous. Interestingly, these guys who had no qualms about cutting into lines at Tibetan monasteries and the Taj Mahal felt it wrong to take photos of the cremation. By the way, their latest entry is about swimming with great white sharks in South Africa where they are now. They left Nepal, went to India and then on to Africa, the last continent of their 7 continent adventure.

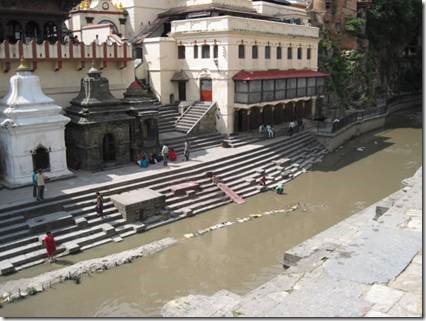

It’s actually a whole complex of buildings most in some form of decay which gives the place a rather compelling attraction. The smoke is from a cremation. The river that runs through the complex is the Baghmati. It runs into the Ganges and then into the Indian Ocean.

We noticed smoke and our guide said that it was a cremation ceremony.

“A shamshan ghat or cremation ground is a platform designed for the cremation of bodies by members of the Hindu faith; Sikhs also use shamshan ghats. Typically, a shamshan ghat is located next to a river, so that the ashes can be cast out and floated away in accordance with Hindu tradition”

http://www.wisegeek.com/what-is-a-shamshan-ghat.htm

The body is covered with straw and then burned.

Our guide said it was acceptable to take photos so I did, though only from across the river. I used my zoom and cropped the photo to focus. Actually, the Pashupati brochure talks about capturing everything in photos and mentions the possibility of viewing a funeral. But our guide couldn’t tell us much about the actual ceremony. While trying to learn a bit to tell you, I came across this article from a faculty member of the University of California-Chico. Amazingly it was a story about her visit to this very same place and she explains the cremation that she saw. The words are hers, the photos are mine.

A Hindu Cremation in Nepal http://www.csuchico.edu/pub/inside/archive/99_02_11/top_story2.html

Editor’s Note: Anthropologist Carolyn Brown Heinz was in Nepal during the last week of a research trip to northern India, where she was researching the lives of women ascetics, when she and her husband, Donald Heinz, dean of HFA, experienced a ritual cremation. She generously agreed to share her story of the event, rare for a Western visitor.

The corpse was wrapped in a white cotton cloth overlaid in an ochre one. A garland of small white flowers stretched along the length of the body. It had been deposited at the top of the steps leading down to the Baghmati River, as if abandoned. No one seemed to be tending to it, no one sat beside it grieving, passers-by did not glance at it. A few yards away women were shampooing their hair and washing pots in the river, indifferent to its presence.

Don and I, however, were electrified. We were to leave Katmandu later in the day, and had come here several times for an opportunity to witness a cremation, but without success. There was almost always a body burning, but we never arrived in time for the ritual itself, when the chief mourner, usually the son, touches the torch to the wood as his supreme and final filial act.

We had spent the previous six weeks down on the plains of North India. I had been interviewing women ascetics at Rishikesh, a sacred city on the Ganges where the river emerges from the first range of the Himalayas. Don was finishing his book on death, The Last Passage (just published by Oxford).

Although seeing corpses being carried to cremation grounds on stretchers accompanied by the slightly frantic chant of “Ram Ram satya hai” is a common sight and sound in any town in India, actually witnessing, let alone photographing, a cremation is not easy. For me, a woman anthropologist, there are gender problems; women do not go to the cremation ground. They stay at home while the men take care of this terrible but essential ritual work. Photographing a cremation is yet another problem; at Banaras no one can get anywhere near a cremation ground with a camera. But here in Katmandu we witnessed our first complete cremation, and it remains among the most moving experiences of my life.

We had stopped at Pashupatinath, an ancient temple complex in Katmandu whose principal deities are Shiva and Kali. The long stretch along the Baghmati River is devoted to cremations. A bridge divides the royal site upriver, from the commoner cremation sites downriver. The Baghmati feeds into the Ganges, which spills out into the Indian Ocean, the ultimate point of dissolution and regeneration for king and commoner alike.

It was on the downstream side of the bridge that we encountered the solitary body, wrapped and waiting for its destruction by flames. Before long, the family arrived, including the widow and daughter. The widow, newly robed in white, stood alone in front of her dead husband and wailed a long, mournful cry. Then she and her daughter were led into an alcove where they could watch and cry in private. The only son, dressed in white dhoti and head scarf and struggling to keep emotional control, awaited the task for which he had been born: to light his father’s funeral fire.

The men, kinsmen and friends of the dead man, did almost all of the ritual work. They lifted the body onto a stretcher so they could purify the corpse in Ganges water. They carried it to the bier and laid the body on top, headed downstream. They opened the shroud to expose his face to the sun, also a god. Each man circumambulated the body, adding ghi [clarified butter] and sprinkling a little purifying water on the face of the corpse. The dead man’s brother broke down in sobs and had to be led into the alcove with the wife and daughter. Finally the son was led forward, clutching a bundle of straw, to do pranam to his father’s feet for the last time. This simple, everyday gesture of respect undid his composure. His face wet and distorted with grief, his hand full of straw shaking so badly they had trouble lighting it with the fire they brought from home, the son had to be assisted to put it to the wood. Slowly he was helped to circle the pyre, laying the flame that would burn his father’s body and release his soul.

This stark Hindu funeral and those I have seen since have deeply impressed me. Once I thought this must be a grotesque custom, but I have come to respect Hindu cremation. No body is ever taken to a sterile lab where its fluids are drained by an expert class of morticians and replaced with chemicals, nor does it lie in a commercial parlor tended by businesspeople. Their way of death is an act of family love and powerful religious ritual. The body is burned within the day of death, the soul is released to new life, and the heat by which the gods brought the universe into being is rekindled.

Carolyn Brown Heinz, Anthropology

There was a legend connected to these small shrines where women could learn how many children they would have.

These people look to be cleaning out the grass that had grown over the stone path.

It was impressive but Randal and I were pretty tired out by this time so just followed our “guide” but not learning a whole lot. And I didn’t pay to take photos of the holy men with Rasta hair and white faces.

The whole complex is divided by the river where people swim and wash clothes and where the dead are cleansed before the cremation and their ashes scattered afterwards.

We walked across the bridge an up the hill overlooking the complex.

The temple of Pashupatinath is located on the western bank of the Bagmati but only practicing Hindus and Buddhists are allowed to enter the temple or even take photos from outside.

We went off to our final stop and really should have just skipped it because we were really too hot and tired and should have saved it for another day. The tickets cost about $4 apiece, not much, but I don’t think we even got our money’s worth. Hanuman-dhoka Durbar Square sounds really interesting when you read its brochure. However, by the time we got there, the museum was closed so that was out. Randal got surrounded by a group of begging 6 year olds while he was trying to eat his ice cream cone and those kids are lucky to still be alive. Lots of the structures that we saw looked like they were falling down and were surrounded by mounds of rubble. We did see “the living goddess” Kumari Devi. We weren’t allowed to take photos of her either. Our guide was pretty impressed that we got to see her when she came to the window of the house she lives in during her time as the living goddess. I have to say that I was more flabbergasted than amazed. I read that there was a recent high court case in Nepal as to whether she should be allowed to attend public school and the answer was yes though she had been being “home schooled.” http://www.visitnepal.com/nepal_information/kumari.php

The following link to an article from the India Times tells the story.

http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/world/south-asia/Nepals-Living-Goddess-passes-acid-test/articleshow/6123697.cms Nepal’s ‘Living Goddess’ passes acid test IANS, Jul 3, 2010, 12.16pm ISTIANS, Jul 3, 2010, 12.16pm IST

KATHMANDU: An extraordinary 15-year-old girl, who never went to school after being chosen as a ‘Kumari’ or ‘Living Goddess’ of Nepal revered by thousands of Hindus and Buddhists, has created history by becoming the first goddess to pass the tough school-leaving examination that leaves thousands floundering every year. Chanira Bajracharya, one of the three ‘Kumaris’ of Kathmandu valley, became even more god-like in the eyes of people on Saturday after the results of the dreaded School Leaving Certificate examination were declared and she was announced to have passed with “distinction”, having secured over 80 percent marks. Chanira, the Kumari of Lalitpur city, becomes the first reigning living goddess to have passed Nepal’s “Iron Gate” examination. It is an extraordinary feat considering that out of the over 385,000 students who took the examination, only 64.31 percent made the grade. In Chanira’s case it is even more extraordinary considering that she never went to school and wrote her test from her official “sacred” chamber in her intricate official robes. The Kumaris, regarded as the incarnation of a Hindu goddess of power, Taleju Bhavani, are selected from a Buddhist community on the basis of 32 auspicious signs, which in the past included having a horoscope compatible with that of the king of Nepal. The Kumaris were also regarded as the protectors of the royal family and the only living beings before whom the monarch humbled himself by bowing down. Chanira, like her peers and predecessors, lives in her own palace where her movements are restricted. The Kumaris are not allowed to walk on the ground and are either carried or tread on a red carpet. Though the teen was enrolled in the Bhasara Secondary School, she never went there to attend classes. Instead, her teachers came to her palace to coach her. When she took the exam in March, it made news worldwide and images of the goddess, arrayed in red and gold clothes with a third eye painted on her forehead were circulated far and wide. After getting her results, the shining-eyed Kumari said she would now take admission in a private college. She is said to be keen to study computer science and Newari, the language of her clan. In the past, she had said she would like to take up a career in banking. Chanira is nearing the end of her reign, since as per tradition a Kumari is replaced before she starts menstruating. A former Kumari, Rashmila Shakya, became a celebrity after she studied computer science and co-authored a book on her life as a goddess, “From Goddess to Mortal”. However, Rashmila went to school only after her reign was over; so did many other Kumaris. The rules were relaxed after 2008 when an advocate challenged the restrictions imposed on the young girls and called them a denial of their fundamental rights. Subsequently, Nepal’s Supreme Court ordered the government to allow the Kumaris to attend school. However, the curbs continue to be there and another Kumari, Sajani Shakya, was “sacked” in an unprecedented move by her priests after her family accepted an invitation for her to go to the US to attend a film festival that showed a film featuring her as well as two other living goddesses.

Our goal was the museum located at the complex. Once we found the museum was already closed we decided to just head on back to our hotel. It was about 5 pm and, anyway, time for our guide and driver to go home. If you follow that link at David and Ronnie’s site, Project – 7 you can read about Durbar Square which they seemed to like. We might have too if we had gone early in the morning and just visited there and the museum and skipped the visit to the Monkey Temple.

http://nepal.saarctourism.org/hanuman-dhoka.html will tell you much more than I can.

My photos from Durbar Square

Kal Bhairav

“This huge stone image of Bhairav represents deity Shiva in his destructive manifestation. It is undated, but was set in its present location by King Pratap Malla (mid 1600s) after it was found in a field north of the city. This is the most famous Bhairav and it was used by the government as a place for people to swear the truth. “From our Durbar Square brochure. The chair is there coincidentally…no one is being made to tell the truth.

This photo of “Kathmandu Mutts” is for my sister’s dog Max who wanted a photo of a Tibetan Lhasa Apso. Somehow I managed not to see one when I went looking for the photo.

In China shoulder poles were used to carry heavy loads and in Tibet, a sort of backpack apparatus. But in Nepal people seemed to use this head strap.

Ru

DoraMac

July 27, 2010