|

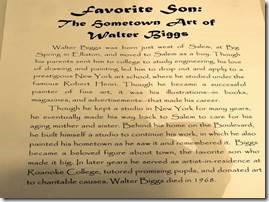

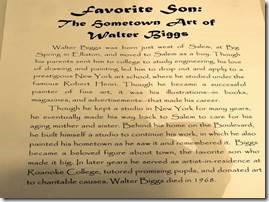

Walter Biggs Remembered: Artist Was Story Teller

by Richard Persinger

Richard Persinger, Salem native and graduate of Roanoke College and the University of Virginia Law School, lives in retirement in Dobbs Ferry, New York, with his wife, Mildred Emory, also a former Salem resident. These are his recollections of Salem artist Walter Biggs.

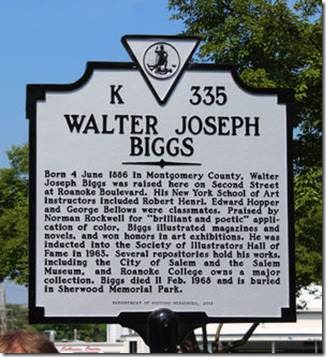

Walter Biggs, 1886 – 1968, had a sufficient reputation as an illustrator and fine arts painter so that his biography has been sufficiently recorded. He was born at Elliston, Virginia, about ten miles west of Salem, Virginia, the two places being joined by U.S. Route 11. I remember traveling through Elliston, which consisted at that time of a very few houses.

He came to New York in 1903 and had a studio there until after the middle 1940’s. After that he moved back to Salem where his mother and sister had lived for many years.

While I lived in Salem, until I left permanently in 1939, I didn’t really know Walter, although the Biggs house was just around the corner from where I lived. Of course, like most people in town, I recognized him on the street when he came for visits about once or twice a year. He was a striking figure — tall, very thin, black hair and a neatly trimmed mustache –the epitome of an artist as a popular ideal during that time.

When I moved to New York, I shared living quarters with Randy Chitwood from Roanoke, Virginia, then a much younger and less well known artist, who for some six or seven years had been studying and painting in New York.

Soon after I arrived, we moved into an apartment on West 68th Street. Neither of us could afford a whole apartment. At the time my income as a law clerk, including unpaid overtime, allowed discretionary expenditures of about seventy-five cents or less a day. That included newspapers, going to a movie now and then, getting my pants pressed and everything else.

Through Chitwood I immediately became a dinner regular, as part of the group eating at a Child’s restaurant located on Amsterdam Avenue, a short distance from our apartment on 68th Street. Every evening about dinnertime, from three to about seven of the group of eight or nine regulars would assemble for dinner more or less together. Almost every evening there were lots of complaints about the food, but the company was great. There were, besides the newcomer, artists, a couple who had a business or renting photos from their extensive library of pictures, a bachelor who had been an engineer, an editor of the Chicago Tribune and a highly successful author of short stories, and, of course, Walter Biggs.

After two years I moved to an apartment on the East Side, but continued to see Walter from time to time. These contacts were much more frequent after the arrival of my new wife, Mildred Emory, when we were married in 1942. Walter had been a good friend of Mildred’s mother and the Emory family for many years.

Besides the conversations during the extensive time I spent in Walter’s company, when I think of him my thoughts quickly go to some of the scores, if not hundreds, of stories that he told.

During this period, when something reminded him of another story he would say — “I’ve probably told you about — “. This was usually accompanied by a very much raised eyebrow. He had a talent for raising an eyebrow so high on his forehead that it gave the impression of going up several inches, turning over one or two times and then falling back into place.

In spite of the many stories he told, I do not think he ever repeated a story. My wife wishes I had the same record.

After spending a good deal of time with Walter, I had never known that he had, you might say, been a professional baseball player. Some time before he had moved to New York, he had played for Richmond or one of the other small cities in the eastern part of Virginia. These teams were organized in the Atlantic League.

He told one story of a game to decide the League Series winner for the year, a game that went into numerous overtime innings. Walter’s team scored a run and pulled ahead. If they could keep their opponents at bat from scoring another run they would win. With two out, an opposing batter hit a long drive that landed just at the perimeter fence. The nearest fielder ran toward the ball. When he got close, his spirits sank. Just where the ball landed by the fence a fence board was missing. The ball was nowhere in sight. He was desperate. Nearby he saw a potato – rather round and about the size of a baseball. He picked it up, threw it in; it was relayed to the catcher and the runner was out at home plate. Walter’s team celebrated winning the series and went home. He never told me the identity of the hero who won that game. I have sometimes wondered whether he was later a well known artist in New York.

Soon after Walter came to New York he had a studio in the Lincoln Arcade, located about where Lincoln Center is now. Walter lived in his studio, where the living arrangements consisted principally of an old steel army cot. He told a story of a painting he was doing, on commission for an illustration, that included a number of human figures. He worked quite a long time on it and, as he neared completion, painted in the skin tones — hands and faces– of the figures. Then he went to sleep on his cot in the studio. Next morning, as he prepared to finish the picture, he was much disturbed to find that the hands and faces of all the many figures were completely bare — no paint, only bare, clean canvas. He was sure he had put in all the skin tones the night before. He painted in the skin tones again and in due course went to bed. Next morning, the same bare spots on the canvas, while the rest of the painting remained untouched. That night, after painting in the skin tones a third time, and after a small dinner staying at all times in sight of the painting, he turned out the lights and sat down on his cot, determined to watch the painting all night. As soon as the light was turned off and the studio was quiet, he watched by the light coming in from the street, many large croton bugs came out of the drain of the sink, rushed to the painting and started eating the fresh paint. Next day, he realized that the paint for the flesh tones had been mixed with glycerin, which those large water beetles evidently considered a great delicacy. A day or two later he delivered the painting which had been elaborately protected in the interval.

My wife and I have been fortunate enough to have a number of Walter’s paintings. These were acquired by gift from Walter, purchase from him or because they were given by Walter to Mildred’s or my parents.

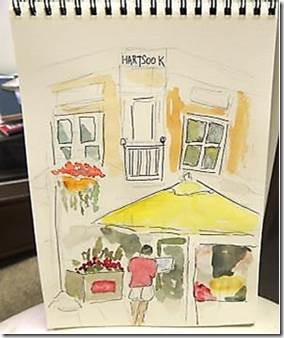

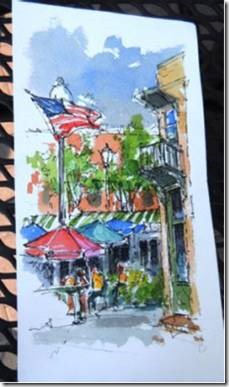

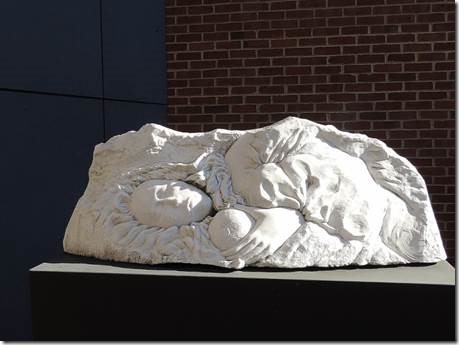

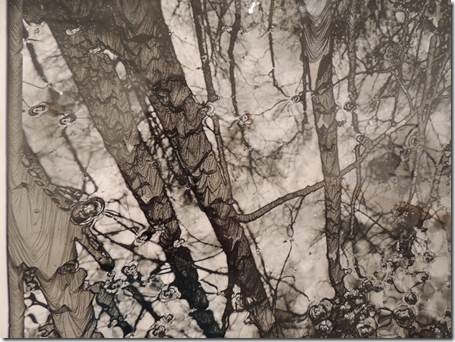

The first one, given us as a wedding present, was a watercolor which had recently won second prize in the Chicago Watercolor Show. The scene is a small street or alley in Charleston, South Carolina, depicting the homes of some black people. Some are leaning out a front window, sitting on the front stoop, or standing in the street. Others are in the street at a distance. Like much of Walter’s work, as the picture becomes more and more familiar, the viewer continues to find more figures and build in more detail as understanding of the scene continues to grow.

While we were living in New York, we suggested that if Walter had time between his other invitations he should have Thanksgiving dinner with us at our apartment. On Thanksgiving, when he arrived at the appointed hour, he pulled from his overcoat pocket a rather crumpled piece of paper, saying that we probably wouldn’t want it. It was a watercolor of the old slave market in Charleston, long since demolished, painted from sketch notes which he had made by moonlight some years earlier.

Of course, we have always treasured this painting and it has always hung on our wall.

Walter never dressed like a modern hippie artist. Always, when I saw him on the sidewalks of Salem long ago and when I knew him in New York, he was carefully dressed — jacket, white shirt and tie — as if about to make an afternoon call on a Southern lady. I never saw him in a painter’s smock or paint-covered work pants. Typically he bought very fine tweed suits and topcoats. He did seem to wear them rather a long time, but if the material might lose a little of its body, the garments still retained the distinctive look of fine clothes. On occasion he might drop a little paint — sometimes oil paint — on his suit. His practice was to let it dry and then scrape it off the fabric with a very sharp knife. The good quality fabric seemed to tolerate this treatment quite well.

Walter’s habit of rather careful dressing did not carry over to neatness in his studio. It appeared that when he finished painting for the day he just quit. On his palette there might be gobs of paint of many colors, open and broken tubes of paint lying about, a few discarded brushes and other debris of the work day.

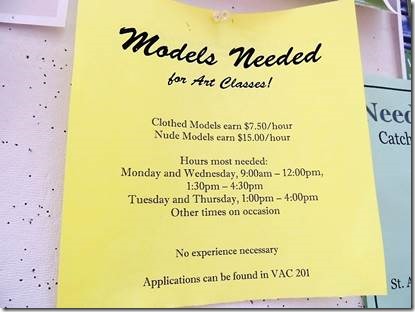

In his studio there was a long-unused fireplace in which were sitting a large number of crockery containers in which were stored what appeared to be literally thousands of used brushes, caked with paint. The high ceiling studio had a large balcony across one end which was filled with trunks, boxes and piles of costumes of all kinds. When he needed a costume for a model he could usually search through the inventory stores on the balcony and find what he needed. He might need an elegant outfit for a gentleman of the days of the three musketeers. It would probably look very bedraggled after years of haphazard storage, but under Walter’s hand guided by his artistic eye it would come out as very elegant indeed.

Walter solved many of life’s problems by ignoring them. Usually this seemed to work out fairly well. After I had seen a number of photographs of the interior of the homes of black people living in the country, some of them showing the kitchen area with the wood fired cook stove, I asked him how he had gotten such good pictures with such limited light. These had been taken around or soon after 1900. It was often difficult to take good time exposures with the camera equipment of that period.

Walter said he had just snapped them with a box camera that someone had given his sister, Lucy.

However long Walter worked on a painting, he was never satisfied that it was finished; that it was the best that it could be. For many years he provided illustrations for stories in the Ladies Home Journal. He was nearly always late for due dates. On one occasion, he painted nine different versions of an illustration for a story scheduled for publication. Finally, after about a year of delay, the frustrated editor called Walter and said he had to have the illustration. Faced with this ultimatum, Walter looked over his nine attempts and selected number two, which he shipped off to be used.

Usually late in finishing his illustrations, Walter had a regular method of making these last minute deliveries. There was no Federal Express or other guaranteed overnight mail. He would wrap a piece of paper around the canvas, take it down to Pennsylvania Railroad Station at 34th Street, give it to a porter on the club car, hand him a dollar and ask him to give it to a messenger from the publisher who would meet the train. Then he would call the publisher in Philadelphia and report that the picture was on the way and should be picked up. This form of special delivery seemed always to be successful.

For a while Walter was involved in an arrangement, which I am sure was unintentional, , that took out of his hands to a large extent the decision as to when a painting was finished. A young woman opened an art gallery on the street floor of West 67th Street where Walter had his studio and living quarters. She very much admired Walter’s work and was eager to have as much of it as possible in her gallery.

She visited his studio frequently and watched closely as he worked. When she decided that a painting was finished, she snatched it away, let the paint dry and put it on exhibition in her gallery — with Walter protesting that it was not finished. This system seemed to work out rather well for a while. I do not know the reason that it was discontinued. Probably Walter did not like anyone organizing him or interfering with the way he did his work.

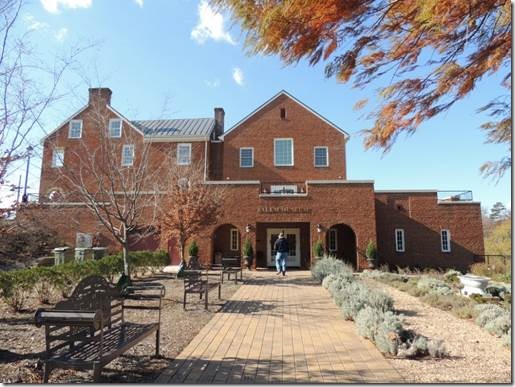

http://www.salemmuseum.org/guide_archives/HSV3N1.aspx#wbiggs

Watercolor

http://www.arcadja.com/auctions/en/biggs_walter/artist/81866/

|